Winter 2003. Walter Reed Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland. As I put the palm of my hand on the door, I could feel its coldness, and feel the cold wave of my own fear, the culmination of days of trepidation and worry about exactly this moment. I pushed the door open and crossed the threshold into someone else’s world of pain.

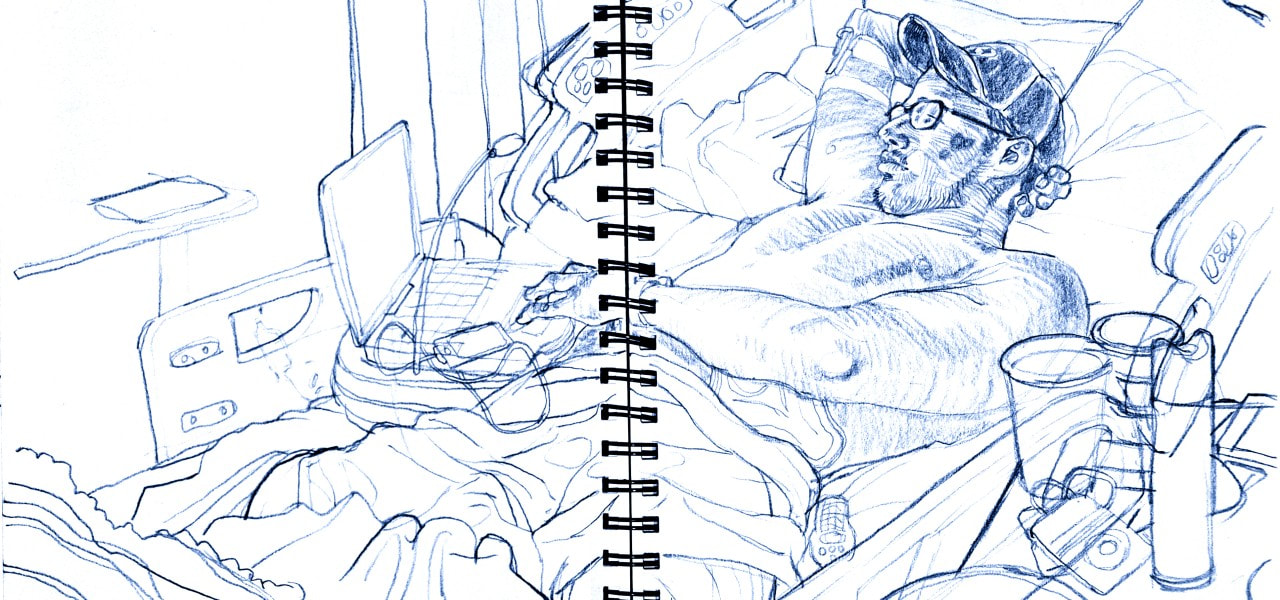

The door swings open and instead of another team of doctors, in walks an artist, or two artists, or three artists. I mean, really? Why wounded warriors don’t throw things at us, and tell us to ‘take a flying expletive at a rolling donut,’ is just amazing to me? But instead we walk in, and, they allow us – welcome us even – inside, inside their pain. They open themselves up to us. They tell us their stories. And we do our best to capture it all. In art.

“It is all fun and games until someone pokes an eye out,” as my old gran used to say as I was doing something stupid as a kid. In this world though, it is all fun and games until an IED takes your leg off, or an arm, or both legs, or both legs and an arm, or it takes your sight, and hearing, and maybe skin. Then maybe it takes your youth, then your vitality, or perhaps your friends, or spouse or partner. It is life changing.

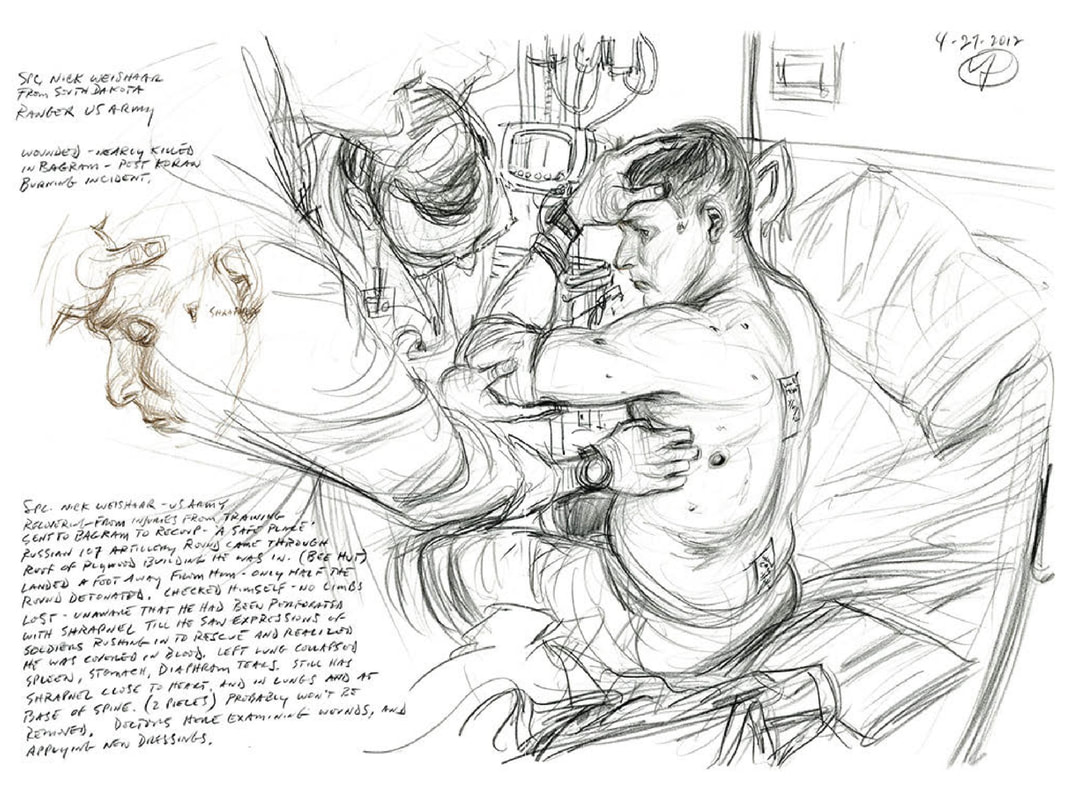

The damage that weaponry of war can inflict is severe, and our increased medical expertise over the last seventeen years of the War on Terror - and its associated spin-offs - has allowed more and more men and women to survive their close encounter with death. Many of the wounded return vastly changed by their experience and dealing with an instant forced-perspective shift of who they are, and what their life will be, and how the world will see them now. Most of the people I interviewed and drew at Walter Reed were still at the apex of their adjustment to their physical change.

My first sit down was with Sgt. Heath Calhoun. He is sitting upright in bed with stumps of his legs lain out in front of him. One is still wrapped in gauze. From the waist up his body is in the peak of fitness and youth. Spine straight. Muscles delineated. Sgt. Calhoun lost both legs above the knee to an RPG in Mosul, Iraq.

Being an artist in these conditions is humbling work. It is also inspiring, and honestly, informative. The biggest challenge other than overcoming that fear of my own possible responses to the horror was the sheer incongruity of what I was doing. What right did I have to turn these unfortunate patriots into art objects?

The answer was in the public response. It was overwhelmingly positive. The first newspaper article which tracked three different men and their families drew a massive response. People wanted to know more. They wanted to know how they could help the wounded. It seemed that the art, in my opinion, reminded people that they needed to care. Forced them to care almost.

Sgt. Calhoun and I have been in contact again recently. You will be pleased to know he is now skiing for the US in the Paralympics. Find him @leglessheath on twitter.

I first met (then Chief Warrant Officer) Michael (Mike) D. Fay when he took an interest in my work from Iraq. Mike is a Marine, and was an active duty USMC artist at the time we met. Mike has done it all. Including four tours as an artist with the Corps between 2000 and 2010. Two in Iraq and two to Afghanistan. He came damn close to becoming a casualty himself last time out, narrowly avoiding an RPG strike in Helmand Province in Afghansitan. Mike’s personality can best be described as effervescent.

Mike is the driving force behind what is the Joe Bonham Project. It was Mike who gathered other artists to him to make the outings to the hospitals, wards, rooms, and lives of the wounded. It was Mike who first saw the need to document and highlight the pain and challenges of those who return from war wounded. It was Mike who organized and cajoled the disparate artists into donating their wounded warrior work to the Joe Bonham Project. It is Mike and his wife Janis who drive the U-Haul that transports the exhibition around the country. It is Mike’s essential drive that has kept the project alive. Put simply, the Joe Bonham Project would not exist without Mike.

Joe Bonham is a fictional character. He is the WWI wounded, faceless protagonist of Johnny Got His Gun, written by Dalton Trumbo in 1939 as an anti-war novel. Through rehabilitation Joe slowly realizes that he has lost all of his limbs, as well as his face, leaving him blind, deaf, dumb, and without smell. Joe is unextraordinary in every capacity save the gravity of his injury. His character is meant to be representative of an every-day, young American man from the period. Joe is trapped within his head without the means to communicate with the outside world. Joe understands, with bitterness, that his injury has granted him a status unlike any other man— he exists on the boundary of life and death. It is a haunting but all too real scenario.

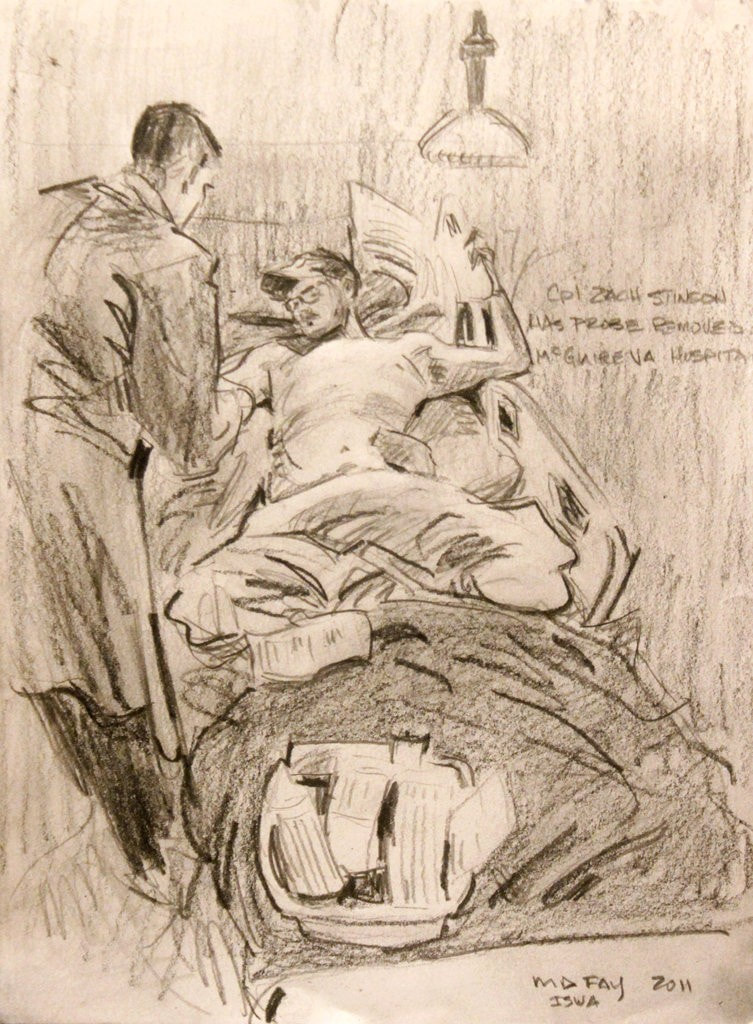

Artist Mike Fay

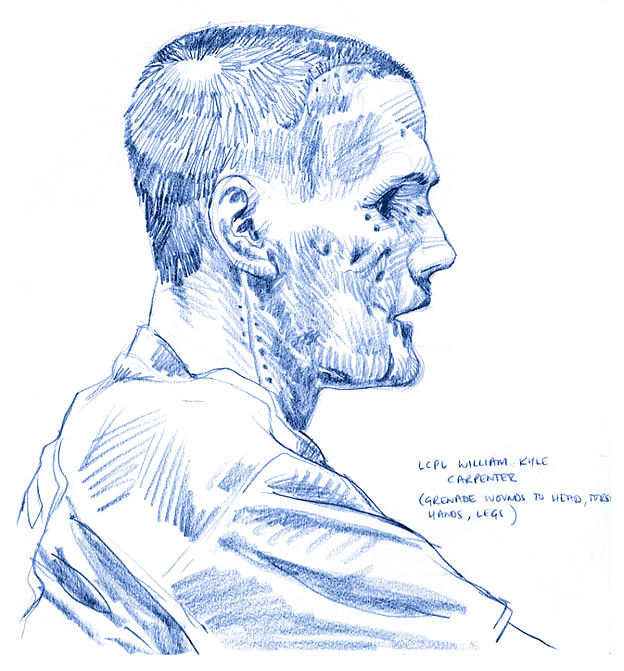

Artist Mike Fay The only trick I have learned to get myself past the incongruity of what we are doing as documentary artists is to turn my emotions off as much as I can while I draw, and concentrate on the accuracy. Even so, Kyle’s wounds were bad. I remember Mike talking in Marine to Marine plain speak. “You really got f’d up,” he said. Kyle laughed at this. It was true. Kyle suffered severe injuries to his face and right arm from the blast. His jaw and right arm were completely shattered. He lost his right eye and most of his teeth. He was in the very beginnings of his recovery at the time. I remember mostly that he was open and willing to endure our invasion of his scant privacy with dignity and poise.

Over the last decade or so Mike’s enthusiasm for the task of wounded reportage, has encouraged and cajoled many other more talented artists to join the group, and visit hospitals to continue the documentation and grow the project. The amazing Victor Juhasz, along with Jeffrey Fisher, Jess Ruliffson and Rob Bates have been major contributors, along with Ray Alma, Emily Bolin, Roman Genn, Fred Harper, Bill Harris, Joshua Korenblat, Steve Mumford, and Joe Olney to name a few.

The art in the Joe Bonham exhibit is unflinching in its gaze, but also very, very human in the lens it is looking through. If you have time, I dare you to show the courage to go and see it during its four or five months at the Combat Art gallery of the National Museum of the Marine Corps in Triangle, Virginia. It opens to the public on Monday.

It will leave you changed.

Author: Richard Johnson

Richard is an USMC combat artist and mentor. While covering USMC operations around the world, he works directly with active duty Marines interested in the USMC Combat Arts program, helping them develop the necessary skills to visually report on the Corps.

See his full bio here.

The Joe Bonham Project group was founded by Mike Fay a former Marine Corps combat artist. The work is dedicated to documenting the grueling journeys of American soldiers who survive the harrowing terrors of combat but do not survive “intact.” The art depicts, with sobering intensity, the challenges for the soldiers who survive. Theirs is an often excruciating journey to reclaim a new life and forge a new relationship with the world as whole human beings – not simply as the sum of their wounds.

The Joe Bonham Project will be on display in the Combat Art Gallery from November 2019 to March 29, 2020.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed