This article was published in Leatherneck Magazine, December 2021.

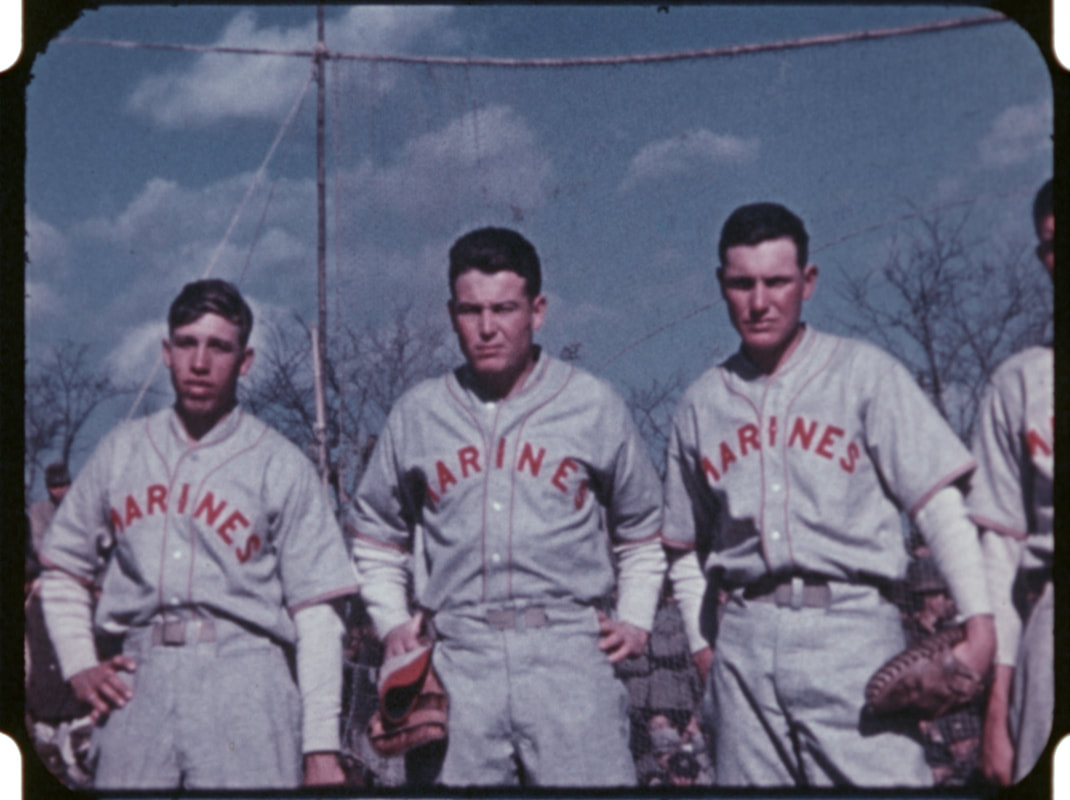

In the Marine Corps archives, there is film footage of a unique baseball game in which a baseball team composed of U.S. Marines played against a Japanese team in Saga City, Japan. The film itself seems to be the only record of the game. The Marines in the film are from

2nd Battalion, 27th Marine Regiment, 5th Marine Division, which fought across Iwo Jima in February and March 1945. Saga City had been rebombed by the U.S. Army Air Forces on Aug. 5, 1945, though the bombing paled in comparison to those of the larger raids that cities like Tokyo suffered. One of the most striking details about the game is the date that the game was played in occupied Japan: Nov. 4, 1945, just a few months after Japan’s surrender. How could the two groups, both terribly affected by the war, come together as good sportsmen for a lighthearted game of ball?

aspect of the occupation where the two former combatants participate in a pastime that they both enjoyed without violence or rancor.

Japan and the United States share a long history of baseball teams traveling to each other’s countries on good will tours, starting when Waseda University’s team toured the United States in 1905. Marine baseball teams faced Japanese opponents as early as 1910 when Waseda University toured Hawaii and took two out of three games from the Marines. Marines also faced Waseda more than a dozen times in China in the 1920s and 1930s. The 4th Marine Regiment’s baseball team embarked on a successful goodwill tour of Japan in 1930, where they played against college and corporate semi-pro teams. In 1927, Waseda University played the powerful Quantico Marines at Quantico, with Japanese Ambassador Tsuneo Matsudaira and Major General Commandant John A. Lejeune in attendance. The Marines emerged victorious with a score of 9-6, but a July 1927 Leatherneck article indicated that it was due to Waseda’s sloppy baserunning as they outhit the Marines 15-12.

WWII impacted baseball in the United States and Japan in different ways. The requirements for manpower by each country’s military strained college and professional sports teams. Young, able-bodied men were needed to serve, and professional baseball leagues in both countries did little to protect their players from service. It was not a foregone conclusion that professional baseball would continue during the war in either country. In the United States, the major leagues, minor leagues and semi-pro leagues did, as did many college baseball teams, with the consent of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, arguing that the entertainment value of baseball was too high and would be good for morale.

In the United States, baseball was considered a morale-building venture that helped Americans endure war rationing. Major League Baseball suffered from the war mobilization effort, losing most of their young talent to the draft. The average age of the players of the Major League increased steadily through the war as younger players left the field for military service. By the end of the 1944 season, many critics thought that Major League Baseball would not last another season. However, the league did survive by using players too old or not physically capable of joining the military.

In 1944, the U.S. Army suggested a plan for a World Series that pitted service teams against each other as a War Bond sales drive. According to the plan, the best-regarded military teams would play a series of games, some on military bases for the benefit of those in the service, and others in town for civilians. The Army wanted to invite the Navy’s Great Lakes team, the U.S. Army’s 20th Armored Division Team and the Parris Island base team. While this plan was not enacted, it demonstrates that the military thought of creative ways to use the popularity of baseball to support the war effort.

In September 1944, the U.S. Navy and U.S. Army put two powerful sides together for the “Servicemen’s World Series.” The series took place in Hawaii and was slated to last seven games, but the series proved so popular that they ended up playing 11 games instead. The Navy walloped the Army, taking the series 8-2-1. The Army invited the Navy to play again the following year, but the Navy had shipped its all-star talent to remote bases in the Pacific to play exhibition games for deployed troops and declined the offer.

While much of the nation’s baseball talent coalesced into a few military super teams, the rank and file continued to play baseball too. Commanders encouraged athletics to help keep their Marines in fighting trim, especially when military training had become too grueling. Athletic officers preparing to embark were warned that while some athletic equipment was available in supply depots in the Pacific, it was best to go and purchase softballs, baseballs, gloves, and bats where they were commercially available and take the equipment with them as there was not enough extra equipment in the supply system to go around. On nearly every island in the Pacific, engineers cleared spaces to make baseball diamonds, and intramural service leagues appeared everywhere.

When 2nd Bn, 27th Marines of 5th Marine Division deployed from Camp Pendleton, Calif., to Camp Tarawa, Hilo, Hawaii, off-duty Marines participated in athletic leagues, including baseball leagues, at the Kamuela Athletic Field. While on duty, they trained to assault Iwo Jima as part of the V Amphibious Corps.

At Iwo Jima, the Marines of the battalion saw some of the most brutal combat of the war. When they were finally pulled off the line, the battle-weary Division was designated to land on Miyako-Jima of the Ryukyu Islands in support of the Okinawa Campaign. Their role in the battle was mercifully called off. The Division was originally slated to recover and train in Guam to prepare for the invasion of the Zhoushan Archipelago off of mainland China. The Marines were elated as they discovered that they would not stop in Guam and instead returned to the familiar Camp Tarawa.

The 2nd Bn, 27th Marines arrived in Japan in late September and were tasked to patrol the area in and around Saga City, the site of the future baseball game. When the 5thMarDiv arrived in Japan, the Division Special Services Office brought athletic equipment with them. Special services personnel built volleyball courts, basketball courts, football fields and baseball fields at every billeting location when possible. They organized inter-unit tournaments, and they estimated that 25 percent of Marines participated in the activities daily.

Athletics played an important part in the occupation, both for the occupying forces to enhance the morale and physical fitness of war-weary combat troops waiting to return home, but also as a welcome distraction for the Japanese people, who had experienced extreme privations during the war. Ted De Bary was an interpreter sent to Tokyo and surrounding cities to survey the damage to the area sustained during the war. In a September 1945 letter to a colleague, De Bary wrote about the devastation in the cities that had been subjected to relentless bombardment. De Bary said that the people in these cities almost always steered the conversation to Major League Baseball and the 1945 season’s pennant races. He believed that to the inhabitants of Tokyo, talking about baseball was more desirable than talking about destruction.

During the late stages of the war, most baseball stadiums in Japan had been converted to house air defense batteries and as equipment marshaling yards. General Douglas MacArthur prioritized the restoration of the stadiums to playing condition. College baseball returned in October 1945 when the Marines’ familiar opponent, Waseda University, played their archrival, Keio University. Professional baseball returned in November with some exhibition games, and the first full season since the start of the war was played in 1946.

On Sept. 22, 1945, a news release by NBC announced an Army baseball team would travel throughout Japan, playing baseball against the Japanese sides, starting with the University of Tokyo. The proceeds from each game were intended to go to war orphans. But the baseball games between American teams and Japanese teams were not necessarily popular. The formal surrender was not even three weeks old.

Quite a few American servicemembers did not approve of the effort, thinking it would show how Americans could easily forgive and forget the atrocities committed by the Japanese military during the war. Army Technical Sergeant Howard Hurwitz wrote a letter to Yank magazine showing his disapproval. A poem that went into syndication in the United States mocked the effort. Often, the American public and servicemembers who did not perform occupation duty in Japan held harsher views of their former enemies than the troops that actually went to Japan. Those in Japan had more sympathy for the civilians in the area after having viewed their appalling living conditions. In November 1945 Marines reported that there were no instances where Japanese military members had violated the terms of the surrender. They also reported excellent compliance with American forces, which further elicited feelings of goodwill.

The game carried a carnival-like atmosphere. The lot at which the game was played was named Antonelli Field, after the battalion’s commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel John Antonelli. Rows of uniformed women marched in and participated in running competitions. There was a Kendo and Judo exhibition performed for the Marines, even though the Allied occupation efforts began to curb these activities in an effort to stamp out militarism. There was a group of women in black uniforms playing drums for the audience. Even though the Japanese government took a hostile stance towards baseball, the Saga team had uniforms that were in good order, and so did the Marines. Throngs of civilians showed up to cheer on their team.

The filmographer at the game worked to capture the event in excellent detail. He set his camera up in different locations to capture various aspects of the game. He filmed the crowds and the scoreboards and a lot of other little details that add to the beauty of this film. After four years of brutal, terrorizing combat, the former foes got together and played a spirited game.

Looking at the game, emotions must have been running high. The Marines wanted to demobilize and go home. The Japanese wanted to put their country back together, but the entertainment-deprived populace relished the opportunity to participate in the day’s festivities and while the Americans took the game with them wherever they went, the Japanese people finally got the game back. It is easy to look at the game as a return to normalcy for both groups of people using the commonly understood universal language of baseball.

By the following year, baseball returned for teams at all levels in both countries. Marine Corps Sports Hall of Famers Gil Hodges, Ted Williams, Jerry Coleman and Ted Lyons exchanged their boondockers for spikes and went back to their Major League clubs to continue their illustrious baseball careers, and the era when the U.S. military fielded the best teams in baseball ended.

MCA Editor’s note: All photos are still images from video number 162591 from the United States Marine Corps History Division collection at the United States Marine Corps Film Repository at the University of South Carolina.

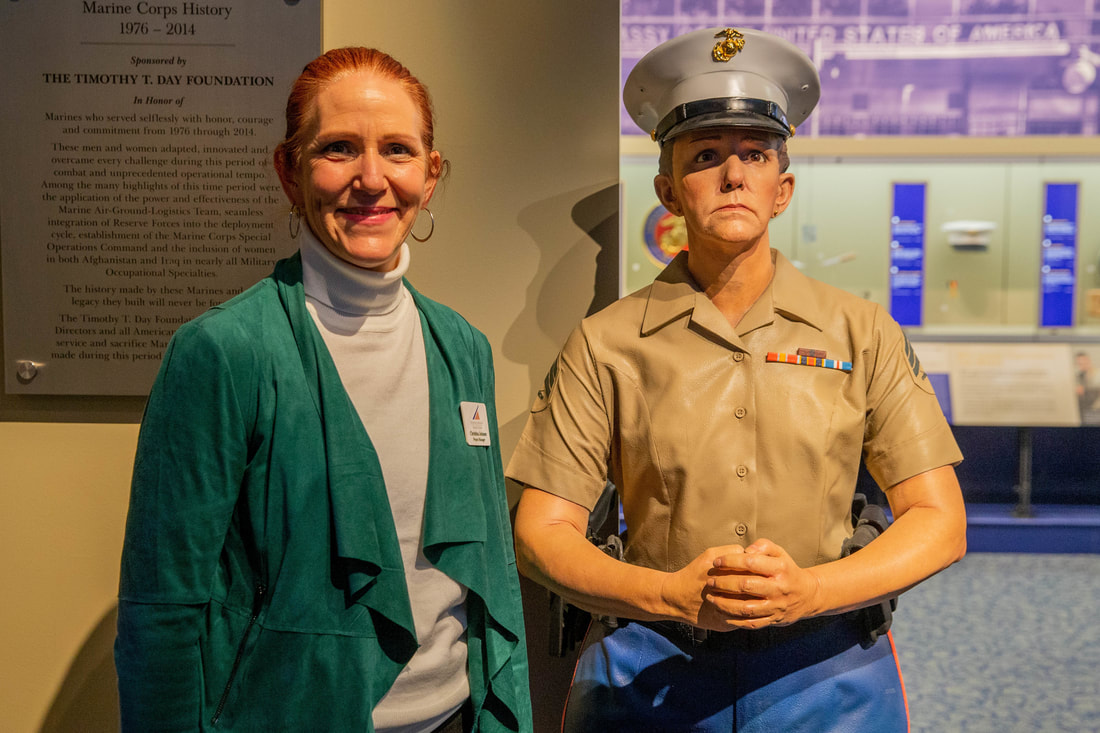

Author: Kater Miller, NMMC Outreach Curator

Kater Miller is the outreach curator at the National Museum of the Marine Corps and has been working at the museum for 11 years. He is developing an interpretive plan for the Marine Corps Sports Gallery as part of the Final Phase expansion underway at the museum. He served in the Marine Corps from 2001-2005 as an aviation ordnanceman.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed