Overview

Effective military communications are a vital part of warfighting. An opponent who intercepts critical messages could determine the enemy’s plans, strengths, and weaknesses.

During World War II, the execution of amphibious assaults demanded secure and reliable communications between the Marines on the beach and the ships supporting them. Navajo Code Talkers proved indispensable in their ability to send and receive encoded messages quickly and accurately, helping to land and consolidate beachheads. But this was not the only area where Navajo Code Talkers proved themselves. At every level of communications on shipboard, during reconnaissance missions and in the heat of battle on the front lines, Navajo Code Talkers were essential to the Marine operations in the Pacific.

Native Americans in the Armed Forces

In World War II, approximately 44,000 Native Americans stepped forward and answered the call to serve, with 723 becoming United States Marines; a little more than 400 of them were Navajo Code Talkers.

Enduring a long history of violence, dispossession, and the destruction of cultures and languages, Native Americans joined the armed services for varied and complicated reasons. Some were motivated by the desire to carry on traditional ideals of warrior-hood. Others were influenced by western assimilation and pressure to conform to Western ideals, while still others exercised their dual patriotism fighting for both the United States and for their tribal homelands, traditional communities, and their people.

The warrior tradition in Native American communities is rooted in the protection of community and land. Although specific traditions vary from tribe to tribe, the basic role of the warrior is one of obligation to his community. Today, Native American veterans continue to hold a special place in their home communities. For the Navajo Nation, the Code Talkers have come to symbolize the spirit of survival, resiliency, and the strength of language and tradition.

Effective military communications are a vital part of warfighting. An opponent who intercepts critical messages could determine the enemy’s plans, strengths, and weaknesses.

During World War II, the execution of amphibious assaults demanded secure and reliable communications between the Marines on the beach and the ships supporting them. Navajo Code Talkers proved indispensable in their ability to send and receive encoded messages quickly and accurately, helping to land and consolidate beachheads. But this was not the only area where Navajo Code Talkers proved themselves. At every level of communications on shipboard, during reconnaissance missions and in the heat of battle on the front lines, Navajo Code Talkers were essential to the Marine operations in the Pacific.

Native Americans in the Armed Forces

In World War II, approximately 44,000 Native Americans stepped forward and answered the call to serve, with 723 becoming United States Marines; a little more than 400 of them were Navajo Code Talkers.

Enduring a long history of violence, dispossession, and the destruction of cultures and languages, Native Americans joined the armed services for varied and complicated reasons. Some were motivated by the desire to carry on traditional ideals of warrior-hood. Others were influenced by western assimilation and pressure to conform to Western ideals, while still others exercised their dual patriotism fighting for both the United States and for their tribal homelands, traditional communities, and their people.

The warrior tradition in Native American communities is rooted in the protection of community and land. Although specific traditions vary from tribe to tribe, the basic role of the warrior is one of obligation to his community. Today, Native American veterans continue to hold a special place in their home communities. For the Navajo Nation, the Code Talkers have come to symbolize the spirit of survival, resiliency, and the strength of language and tradition.

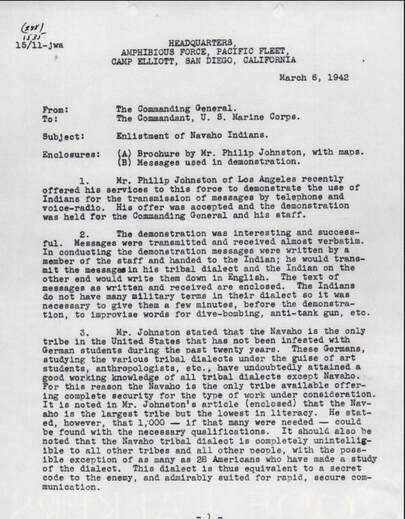

| The Navajo Code Talker Program Among the Navajos in the Southwestern United States during the 1930s and early 1940s, there lived a handful of non-Native people, mostly traders, missionaries, and U.S. Government employees. When war first broke out in Europe, using Navajos for their language was frequently discussed in these circles. Philip Johnston, the son of a missionary who grew up on the Navajo Nation, brought this suggestion to the Marine Corps in February 1942. By April 1942, twenty-nine young Navajo men volunteered for a special assignment. This pilot group became Platoon 382, the first all-Indian, all-Navajo platoon in the history of the Marine Corps Recruit Depot, San Diego. After completing boot camp, they transferred to communications training and were joined by four more Navajo Marines. Together, they created the first Navajo code, consisting of 211 words that corresponded to military equipment, ranks of officers, Marine Corps organization, names of countries, a general vocabulary, and the coded English alphabet. Over time, more terms were added bringing the Navajo code to nearly 700 words by the end of the war. The Navajo code itself is deceptively simple, yet far more complex than it appears. The original pilot group utilized several techniques that established the framework for later additions. One of these techniques was simple substitution in which one word was used for another word. Another method was compounding, a process used to create new words with a coded meaning. The Navajo Code Talkers developed a coded alphabet similar to the NATO phonetic alphabet. (This universally-adopted phonetic spelling alphabet was implemented by the North American Treaty Organization (NATO) in 1956 to clearly communicate words or letters across languages.) The Navajo version, however, was double-coded As the code grew, so did the number of men in the program. Two of the original Code Talkers, Johnny Manuelito and John Benally, became the first instructors in the new Navajo code school. Monthly quotas were established to maintain regular recruitment of Navajos. Eventually, 420 men completed Code Talker training and more than 400 passed and became Navajo Code Talkers, Military Occupational Specialty (MOS) 642. As a vital part of every major operation in the Pacific, the Navajo Code Talkers were strategically placed in units and special regiments throughout the Marine Corps at all levels. Following the battle of Iwo Jima, Maj Howard Conner, 5th Marine Signal Officer of the 5th Marine Division stated, “During the first 48 hours, while we were landing and consolidating our shore positions, I had six Navajo radio nets operating around the clock. In that period alone, they sent and received over 800 messages without error.” Although the use of Native American languages was not unique to the Marine Corps, the Navajo Code Talker program was. It remains the largest and most successful program to have employed Native Americans as combat communicators. |

|

Post-World War II

Post-war America offered little change for Native Americans. Although U.S. citizenship was granted to Native Americans in 1924, barriers to employ their full rights as citizens existed, and overcoming them remained an uphill battle. The right to vote for all Native Americans was not granted until 1962. Native American veterans who chose to finish high school faced the same federal policies mandating assimilation and prohibiting them from speaking their native languages in the Indian boarding schools.

As the Navajo Code Talkers returned home, however, they continued to move forward with their lives. Many participated in traditional ceremonies to cleanse themselves of the war. Other Navajo Marines returned to live quietly in their traditional homeland, or they sought opportunities in new jobs on and off the reservation. A few Code Talkers pursued college and technical degrees through the GI Bill. Many former Navajo Code Talkers became tribal and community leaders.

The invaluable contribution made by the Navajo Code Talkers was first recognized in 1969 by the 4th Marine Division Association in Chicago, one year after the declassification of the Navajo code. In 1971, following a gathering of Navajo Code Talkers in Window Rock, Arizona, the capital of the Navajo Nation, the men formed the Navajo Code Talkers Association. Carl Gorman, one of the original first twenty-nine code talkers, designed the official logo. Inspired by a sand painting from a traditional protection ceremony for young men going to war, the symbol he chose represents a “listening device” that warned the Navajo Hero Twins of danger during their journey to visit their father, the Sun.

Following a number of local and regional honors and awards, the Navajo Code Talkers finally received national recognition in 1980 with a Presidential Proclamation by Ronald Reagan. In 1981, a commemorative all-Navajo platoon, Platoon 3043, was recruited by the Marine Corps. The following year, the states of Arizona and New Mexico declared a day of honor for the Navajo Code Talkers and introduced a bill to recognize them on a national level. President Reagan declared August 14, 1982, as National Navajo Code Talkers Day. In 2001, the Code Talkers were awarded Congressional Gold and Silver medals for their instrumental role in World War II.

Post-war America offered little change for Native Americans. Although U.S. citizenship was granted to Native Americans in 1924, barriers to employ their full rights as citizens existed, and overcoming them remained an uphill battle. The right to vote for all Native Americans was not granted until 1962. Native American veterans who chose to finish high school faced the same federal policies mandating assimilation and prohibiting them from speaking their native languages in the Indian boarding schools.

As the Navajo Code Talkers returned home, however, they continued to move forward with their lives. Many participated in traditional ceremonies to cleanse themselves of the war. Other Navajo Marines returned to live quietly in their traditional homeland, or they sought opportunities in new jobs on and off the reservation. A few Code Talkers pursued college and technical degrees through the GI Bill. Many former Navajo Code Talkers became tribal and community leaders.

The invaluable contribution made by the Navajo Code Talkers was first recognized in 1969 by the 4th Marine Division Association in Chicago, one year after the declassification of the Navajo code. In 1971, following a gathering of Navajo Code Talkers in Window Rock, Arizona, the capital of the Navajo Nation, the men formed the Navajo Code Talkers Association. Carl Gorman, one of the original first twenty-nine code talkers, designed the official logo. Inspired by a sand painting from a traditional protection ceremony for young men going to war, the symbol he chose represents a “listening device” that warned the Navajo Hero Twins of danger during their journey to visit their father, the Sun.

Following a number of local and regional honors and awards, the Navajo Code Talkers finally received national recognition in 1980 with a Presidential Proclamation by Ronald Reagan. In 1981, a commemorative all-Navajo platoon, Platoon 3043, was recruited by the Marine Corps. The following year, the states of Arizona and New Mexico declared a day of honor for the Navajo Code Talkers and introduced a bill to recognize them on a national level. President Reagan declared August 14, 1982, as National Navajo Code Talkers Day. In 2001, the Code Talkers were awarded Congressional Gold and Silver medals for their instrumental role in World War II.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Books

Young Adult/Children’s Books

Links of Interest:

Navajo Code Talkers:

https://navajocodetalkers.org

https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/n/code-talkers.html

https://americanindian.si.edu/education/codetalkers/html/chapter4.html

Books

- Holiday, Samuel & Robert S. McPherson. Under the Eagle: Samuel Holiday Navajo Code Talker, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2013.

- Nez, Chester & Judith Schiess Avila. Code Talker. New York: Dutton Caliber, 2011.

- Paul, Doris. Navajo Code Talkers. Pittsburgh: Dorrance Publishing Co., 1972; Anniversary ed., 1998.

- Tohe, Laura. Code Talker Stories. Tucson: Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2012.

Young Adult/Children’s Books

- Aaseng, Nathan. Navajo Code Talkers: America’s Secret Weapon in World War II, New York: Bloomsbury, 1992. Reprinted with Forward by Roy O. Hawthorne, Navajo Code Talker, 2002.

- Durrett, Deanne. Unsung Heroes of World War II: The Story of the Navajo Code Talkers, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009. First published c.1998 Facts on File.

- Hoagland Hunter, Sara. The Unbreakable Code, Cooper Square Publishing, 1996.

Links of Interest:

Navajo Code Talkers:

https://navajocodetalkers.org

https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/n/code-talkers.html

https://americanindian.si.edu/education/codetalkers/html/chapter4.html

RSS Feed

RSS Feed