Guest Blogger: Combat Artist, Richard Johnson

Winter 2003. Walter Reed Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland. As I put the palm of my hand on the door, I could feel its coldness, and feel the cold wave of my own fear, the culmination of days of trepidation and worry about exactly this moment. I pushed the door open and crossed the threshold into someone else’s world of pain.

The door swings open and instead of another team of doctors, in walks an artist, or two artists, or three artists. I mean, really? Why wounded warriors don’t throw things at us, and tell us to ‘take a flying expletive at a rolling donut,’ is just amazing to me? But instead we walk in, and, they allow us – welcome us even – inside, inside their pain. They open themselves up to us. They tell us their stories. And we do our best to capture it all. In art.

“It is all fun and games until someone pokes an eye out,” as my old gran used to say as I was doing something stupid as a kid. In this world though, it is all fun and games until an IED takes your leg off, or an arm, or both legs, or both legs and an arm, or it takes your sight, and hearing, and maybe skin. Then maybe it takes your youth, then your vitality, or perhaps your friends, or spouse or partner. It is life changing.

The damage that weaponry of war can inflict is severe, and our increased medical expertise over the last seventeen years of the War on Terror - and its associated spin-offs - has allowed more and more men and women to survive their close encounter with death. Many of the wounded return vastly changed by their experience and dealing with an instant forced-perspective shift of who they are, and what their life will be, and how the world will see them now. Most of the people I interviewed and drew at Walter Reed were still at the apex of their adjustment to their physical change.

My first sit down was with Sgt. Heath Calhoun. He is sitting upright in bed with stumps of his legs lain out in front of him. One is still wrapped in gauze. From the waist up his body is in the peak of fitness and youth. Spine straight. Muscles delineated. Sgt. Calhoun lost both legs above the knee to an RPG in Mosul, Iraq.

Winter 2003. Walter Reed Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland. As I put the palm of my hand on the door, I could feel its coldness, and feel the cold wave of my own fear, the culmination of days of trepidation and worry about exactly this moment. I pushed the door open and crossed the threshold into someone else’s world of pain.

The door swings open and instead of another team of doctors, in walks an artist, or two artists, or three artists. I mean, really? Why wounded warriors don’t throw things at us, and tell us to ‘take a flying expletive at a rolling donut,’ is just amazing to me? But instead we walk in, and, they allow us – welcome us even – inside, inside their pain. They open themselves up to us. They tell us their stories. And we do our best to capture it all. In art.

“It is all fun and games until someone pokes an eye out,” as my old gran used to say as I was doing something stupid as a kid. In this world though, it is all fun and games until an IED takes your leg off, or an arm, or both legs, or both legs and an arm, or it takes your sight, and hearing, and maybe skin. Then maybe it takes your youth, then your vitality, or perhaps your friends, or spouse or partner. It is life changing.

The damage that weaponry of war can inflict is severe, and our increased medical expertise over the last seventeen years of the War on Terror - and its associated spin-offs - has allowed more and more men and women to survive their close encounter with death. Many of the wounded return vastly changed by their experience and dealing with an instant forced-perspective shift of who they are, and what their life will be, and how the world will see them now. Most of the people I interviewed and drew at Walter Reed were still at the apex of their adjustment to their physical change.

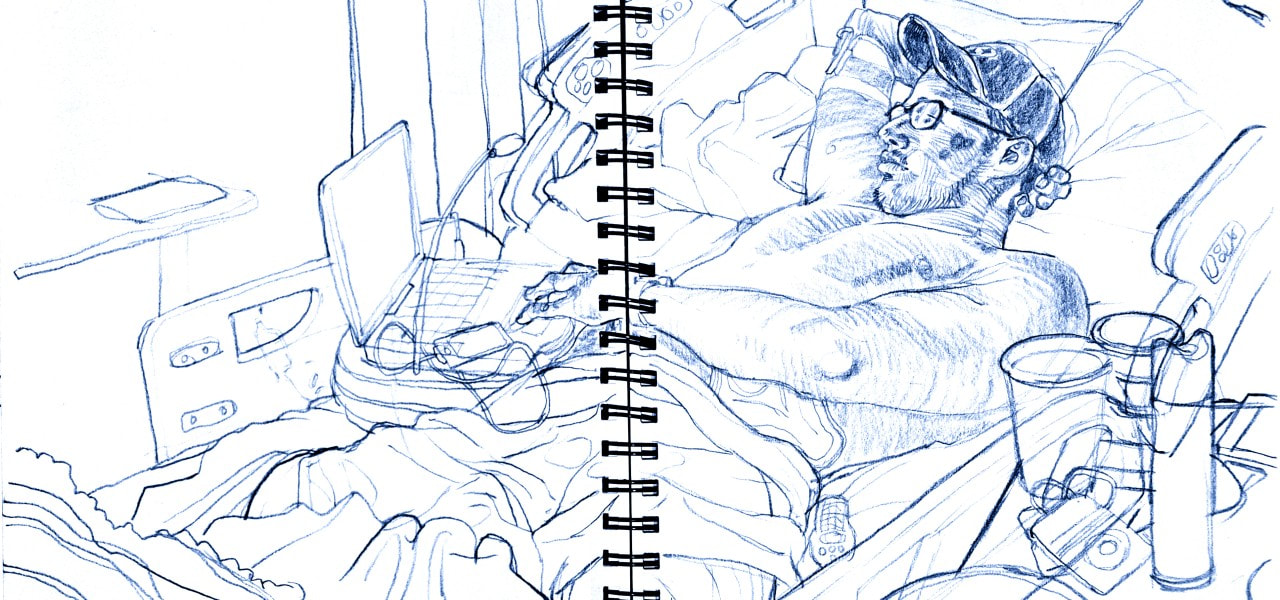

My first sit down was with Sgt. Heath Calhoun. He is sitting upright in bed with stumps of his legs lain out in front of him. One is still wrapped in gauze. From the waist up his body is in the peak of fitness and youth. Spine straight. Muscles delineated. Sgt. Calhoun lost both legs above the knee to an RPG in Mosul, Iraq.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed