End of World War II in the Pacific: 14-15 August 1945

By Mike Westermeier, Exhibit Curator

Woodrow M. Kessler

Woodrow M. Kessler The last weeks of August 1945 were extraordinary for as it seemed WWII was finally coming to an end. That was especially true for those held as Japanese prisoners of war, who found themselves elated yet still uncertain of their future. Such was the case with Marine 1stLt Woodrow M. Kessler.

Kessler began the month of August 1945 at a coal mine near Nisi Ashibetsu, Hokkaido, Japan, focused on acquiring enough food to survive. He had been a prisoner of the Japanese since 23 December 1941, when Japanese Special Naval Landing Force troops captured Wake Island and forced the 1st Marine Defense Battalion, along with detachments from Marine Fighter Squadron 211, the U.S. Navy, the U.S. Army, and several hundred U.S. civilian construction contractors, to surrender. Since then, he had suffered through a torturous ten-day journey in the hold of a Japanese prisoner transport ship, interned in a camp in China, and later suffered a harrowing train ride through Manchuria into Korea where he and his fellow prisoners nearly starved to death in cramped box cars. He arrived in Japan in July 1945, and was cut off from any news of the war until a British prisoner passing Kessler’s work group on 8 August 1945 whispered, “Old Joe is in.”[1]

“Old Joe” was a British nickname for Joseph Stalin, leader of the Soviet Union. The Soviet Red Army launched a massive land and sea invasion against Manchuria, Korea, and Sakhalin Island on 8 August 1945 after declaring war on Japan on 7 August 1945. The Soviet Union had adhered to its non-aggression pact with Japan for the duration of its war against Nazi Germany from 22 June 1941 to 9 May 1945, but declared war after the U.S. Army Air Forces B-29 Superfortress Enola Gay dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan on 6 August 1945. The Japanese high command was forced to confront the fact that they would soon be overwhelmed by Allied ground forces as their empire crumbled and their cities faced the threat of nuclear annihilation from the air after a second atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki on 9 August 1945. Japanese Emperor Hirohito decided to accept the Allied demands for surrender on the evening of 14 August 1945 and prepared to address the nation directly for the first time during his reign on 15 August 1945.

Kessler and the other prisoners at Nisi Ashibetsu were locked in their barracks on the morning of 15 August as the guards and camp commander gathered to listen to the Emperor. Later that evening, the prisoners attended a special dinner at the mining company office , and were later informed by a Japanese officer that the war was officially over. The next morning the prisoners awoke to find that their guards had neatly stacked their rifles outside the prisoner barracks. Kessler and some other prisoners wandered into town and heard Gen Robert L. Eichelburger, USA, Commander of the U.S. 8th Army, broadcasting a message for all prisoners in Japan to return to their barracks, paint the letters “PW” on the roof, and await U.S. air drops of badly needed food, clothing, and medical supplies. The prisoners acquired cans of yellow paint, and soon supplies of soap, clothes, boots, candy, and canned food rained down from the skies. Kessler filled his belly for the first time in years, bartered with the local Japanese villagers for chickens and eggs, and eagerly awaited the arrival of U.S. forces on mainland Japan.[2]

III Amphibious Corps commander MajGen Keller E. Rockey, USMC, designated BGen William T. Clement, USMC, as the head of the combined Fleet landing force for TF 31. MajGen Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr., commander of the 6th Marine Division, chose the 4th Marine Regimental Combat Team to join TF 31 as the first American combat unit to set foot on the Japanese home islands. This choice was symbolic, since the 4th Marines of 1945 was actually a reactivation of the 4th Marines that had temporarily ceased to exist after they were captured by the Japanese at Corregidor in the Philippines in 1942. The regiment was reactivated 1 February 1944, joined the 6th Marine Division, and subsequently fought in New Georgia, Bougainville, Northern Solomons, the Bismarck Archipelago, Guam, and Okinawa. The 4th Marines set sail from Guam on 15 August 1945 and joined TF 31 on 20 August 1945.[4]

TF 31 arrived in Tokyo Bay on 28 August 1945 and began landings to secure strategic areas at Yokosuka Naval Base and shore defenses on 29 August 1945. TF 31 also began liberating Allied prisoners in the area. Over the next two weeks over 14,000 Allied prisoners were liberated, including members of the 4th Marines captured in the Philippines in 1942. Four days after the Japanese signed the instrument of surrender aboard the USS Missouri on 2 September 1945, the “new” 4th Marines invited members of the “old” 4th Marines, that were healthy enough, to attend a regimental guard mount at Yokosuka Naval Base in their honor. Clements said in an address to the assembled 4th Marines, “We’re damned glad to have you here. Some of you have changed a bit since I last saw you, but this is the happiest moment of my life to bring you back to 4th Marines.” The members of the “old “4th Marines boarded trucks after the regimental guard mount and proceeded to the harbor to begin their long journey back home.[5]

“During our nearly four years of imprisonment, we often discussed our misfortune as trained professionals to be so ineffective and lost to the war effort. It was very frustrating. Our only consolation was that if it had not been us, it would have been someone else. We had done our best when we had the opportunity,” Kessler wrote in “To Wake Island and Beyond Reminiscences” in 1988.

Kessler remained in the Marine Corps, served in Korea, and ultimately retired as a brigadier general in September 1955.[7]

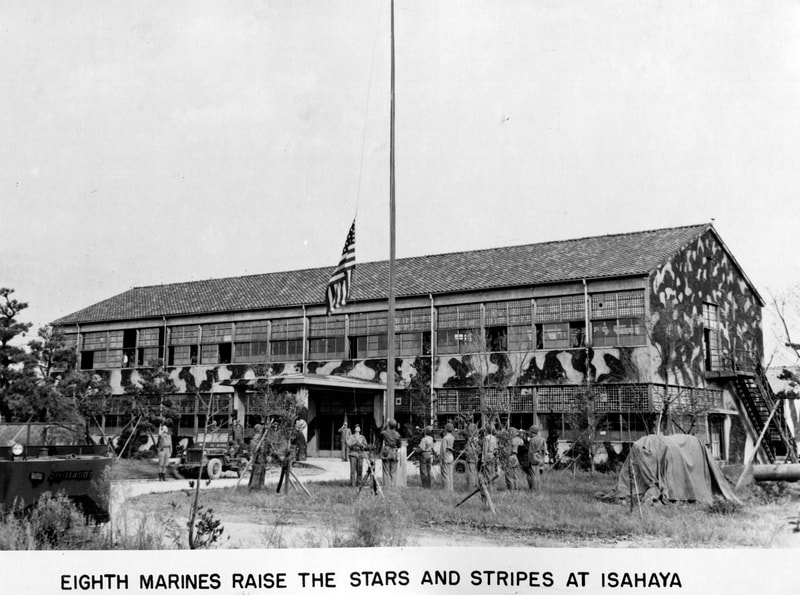

Marines continued to serve as part of the Allied occupation of Japan through June 1946. Their duties included providing security to the Japanese population, facilitating the return of demobilized Japanese soldiers and Japanese civilians displaced from parts of the former Japanese overseas colonies, and the destruction of Japanese military equipment as part of the de-militarization campaign. While many of the Marines surely felt glad to leave Japan behind, many would see it again in four short years when the Marines passed through Japan to fight against North Korea in 1950.

Read more about BGen Kessler in the Marine Corps History Division publication, To Wake Island and Beyond: Reminiscences.

[2] Charles R. Smith, Securing the Surrender: Marines in the Occupation of Japan, (Washington: History and Museums Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1997), 1-3.

[3] Smith, Securing the Surrender: Marines in the Occupation of Japan, 3-5. Brigadier General Clement also had a long personal history with the 4th Marines. He served with them as a young Marine officer in Peking, China, during the 1920s and was quartered on Corregidor alongside the 4th Marines while serving as a liaison officer between the Commandant, 16th Naval District, the Commanding General, U.S. Forces in the Far East, and U.S. forces engaged against the Japanese on Bataan. Brigadier General William T. Clement was ordered to leave Corregidor for Australia aboard the submarine USS Snapper (SS-185) in April 1942 and thus narrowly avoided capture by the Japanese. He was later awarded the Navy Cross for his tireless efforts in organizing the disparate U.S. Marine and Naval forces in Cavite and on the Bataan Peninsula.

[4] Smith, Securing the Surrender: Marines in the Occupation of Japan, 3-5. Brigadier General Clement also had a long personal history with the 4th Marines. He served with them as a young Marine officer in Peking, China, during the 1920s and was quartered on Corregidor alongside the 4th Marines while serving as a liaison officer between the Commandant, 16th Naval District, the Commanding General, U.S. Forces in the Far East, and U.S. forces engaged against the Japanese on Bataan. Brigadier General William T. Clement was ordered to leave Corregidor for Australia aboard the submarine USS Snapper (SS-185) in April 1942 and thus narrowly avoided capture by the Japanese. He was later awarded the Navy Cross for his tireless efforts in organizing the disparate U.S. Marine and Naval forces in Cavite and on the Bataan Peninsula.

[5] Smith, Securing the Surrender: Marines in the Occupation of Japan

[6] Kessler, To Wake Island and Beyond: Reminiscences, 143

[7] Brigadier General Woodrow M. Kessler Biographical File, Historical Resources Branch, Marine Corps History Division.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed