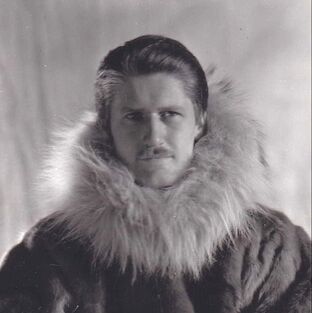

Ferranto in Antarctica

Ferranto in Antarctica

As an artifact, it is unassuming. Twenty-five scraps of paper, yellowed by age and exposure, fixed on a red background. A casual glance could never reveal that these scraps tell an extraordinary story. It is a story that ranges from Antarctica to Guadalcanal to the remote northern wilds of the Korean peninsula. It is a story about radios, wars, and the United Nations. It is a story of the grit and resourcefulness of a solitary, wounded hostage. In short, it is the story of Marine Felix L. Ferranto.

Early Years

Ferranto enlisted in the Marine Corps in August 1933 and trained as a radio operator. In the late 1930s he served a tour of duty at the American Legation in Peiping, China. While there, he was the tenant of a local woman who taught him a little of her language. Although he could not have known it at the time, this knowledge would one day save his life.

In 1939, Ferranto volunteered for the Antarctic Expedition under Admiral Richard Byrd. He was one of four men chosen from hundreds across the U.S. to crew the new Antarctic Snow Cruiser in this venture, for which he would be awarded a Congressional Gold Medal.[i] As the designated radio operator for the Cruiser on an expedition through extreme weather and terrain far from any kind of civilization, Ferranto honed his skills at on-the-fly maintenance and repair. This would come in handy when he returned to his Marine unit and was sent into battle at the advent of the Second World War.

In August 1942, Ferranto went ashore with the 1st Signal Company, 1st Marine Division in the first waves of combat on Guadalcanal. On D+1, his unit captured a Japanese communication and control center, and Ferranto himself repaired the damaged radio equipment within.[i] This transmitter station would become the nerve center of the famous Cactus Air Force, and its operation was made possible by Ferranto’s work in deciphering the Japanese radio markings and returning the pieces to full function.

His actions earned him a battlefield promotion to Marine Gunner, a warrant officer rank. He spent the postwar period in various radio and signal officer positions on the west coast, until he was once more ordered overseas in 1950. At nearly forty years old, having climbed from enlisted to officer rank over an already-colorful seventeen years in the Marine Corps, Ferranto was about to embark on the most harrowing ordeal of his career.

He arrived in Korea on the first day of the Inchon Landing in September 1950. By November, Ferranto was a Radio Relay Platoon Commander deployed with the forward echelon at Koto-ri, deep into the north. At 0730 on the bitterly cold morning of 28 November 1950, he left his relay station alone and headed north for the 1st Marine Advanced Division Command (ADC) at Hagaru-ri.[i] Unknown to both Ferranto and U.N. intelligence, the region was already saturated with Chinese troops, who had infiltrated from across the northern border and established roadblocks on every route of travel as the opening gambit in their Second Phase Offensive.

Only a couple of miles beyond the perimeter of his station, Ferranto came under heavy fire. He turned his jeep around to return to Koto-ri, but did not make it far before a bullet struck his lower left leg. The bullet mushroomed and splintered after hitting bone, pulling bone fragments with it as it tore through the leather of Ferranto’s boot. This made it impossible for him to use the clutch to drive the jeep. Nevertheless, he continued to make his way back south until his jeep was finally blown off the road by a grenade. Ferranto was captured by Chinese soldiers almost within sight of his hilltop radio relay station. Unable to walk on his shattered leg, he later observed wryly that at this point he knew he had “signed on for a two year tour of duty”[ii] as a hostage – a tour he had never anticipated when he arrived in Korea and one that would be extended, month by month, until the conflict and his captivity terminated nearly three years later.

Helpless to contact his unit or the nearby 11th Marines, Ferranto watched the Battle of the Chosin Reservoir begin from atop the ice of the reservoir itself as he was moved deeper behind enemy lines, heading north over the Yalu river into Manchuria.

Prisoner of War

His early treatment was comparatively decent. He was able to communicate with his captors thanks to the rudimentary Chinese he had learned during his time at the embassy in Peiping, and he was afforded some small generational respect because of his age – just a week short of forty years old at the time of his capture. He spent about six months with a Chinese hospital group of wounded prisoners, during which time he received provisional treatment for his wounded leg, equal though meager rations, and even a small stipend of money. After yelling at a Chinese guard who woke him unnecessarily from his sleep, however, this goodwill ended, and in the spring of 1951, he was returned to Korea and the far more brutal control of North Korean soldiers.

Ferranto was among the first of 221 Marines taken into captivity during the course of the Korean War.[iii] He was held until the release of the last group of hostages on the last day of the last prisoner exchange in 1953. All told, he spent nearly 34 months as a hostage, the majority of which were spent in solitary confinement or in isolation with only one or two other men. The wound in his leg, never fully healed, became severely and chronically infected with osteomyelitis as he limped from prison camp to prison camp.

Ferranto and the other hostages endured brutal abuse, coercion, humiliation, malnutrition, disease and infection, inadequate medical care and sanitation, constant threats and interrogation, and hard labor. Because Korea was not a declared war, Ferranto was not protected by United Nations conventions on the treatment of prisoners of war – in fact, he was not even classified as a prisoner of war, and was instead deemed a “police action hostage” in all official correspondence regarding his internment.

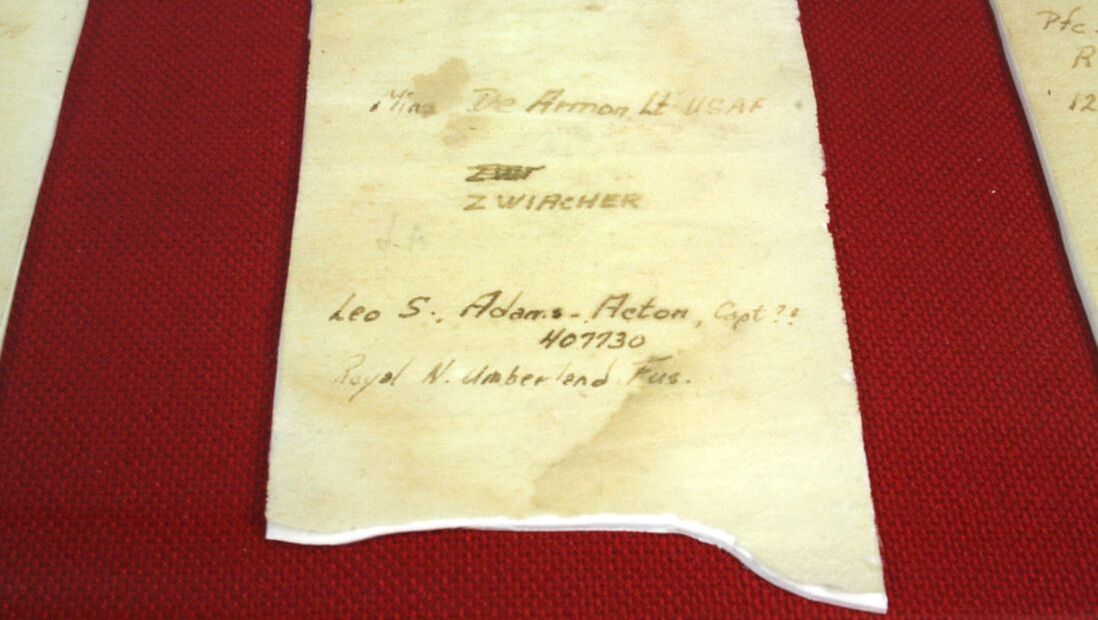

Cigarette Papers

During his time in captivity, Ferranto accumulated cigarette papers through the meager rationing from his Korean guards. On them he wrote the names of other prisoners whom he encountered in the camps when he was not in solitary confinement. These name lists were not uncommon among prisoners – in the fog of secrecy, lies, and psychological pressures in the camps, there was general concern that the Communists might attempt to deny the existence of certain prisoners, or attempt to secretly retain them after the end of the war.[iv] These name lists were, of course, contraband, and any that were found by Chinese or Korean guards were seized and destroyed. Ferranto had created several that were taken from him in surprise searches.

Just a month prior to his release, however, Red Cross packages were distributed to the hostages that contained American cigarettes, a safety razor set, comb, and two tubes each of toothpaste and shaving cream.[v] Desperate or inspired, or perhaps a bit of both, Ferranto brought his considerable ingenuity to bear on the situation. He tightly rolled his last lists of prisoner names and covered them with the plastic wrapping of the new pack of American cigarettes. He then opened one of the shaving tube containers from the bottom, inserted the rolled lists, and resealed the tube. The shaving cream tube and its hidden lists made it out of the camp untouched, and it is these same cigarette papers that have made their way to the collection of the National Museum of the Marine Corps.

The cigarette papers were thin to begin with. Time and exposure to light have further faded the writing on these sensitive artifacts, making them a significant conservation challenge. They contain the names, ranks, and service branch (both U.S. and otherwise), and in some cases the addresses of prisoners Ferranto knew to be held in captivity. Additional markings in some places indicate the date of capture, the date of death, or the last time Ferranto saw the prisoner alive and their physical condition at the time.

Ferranto crossed the border of Freedom Village at Panmunjom on 6 September 1953 and began the long transition back to life at home. He remained in the Marine Corps upon his return to the U.S., although his next several years on active duty were interrupted by frequent and prolonged periods of hospitalization. He required treatment for osteomyelitis, and further spells of blinding head pain led to diagnoses of “POW Syndrome” and psychogenic neuroses. He underwent a craniotomy to address the effects of multiple direct head traumas and concussions received while imprisoned, and was ultimately placed on the temporary disability retired list in 1958 on the strength of “postoperative neuralgia, subjective tinnitus, and unsteadiness.”[vi]

Throughout this process Ferranto faced another battle – an administrative one. While seeking clarification of his disability status, Ferranto was informed that the cause of his injuries was “not established by the available medical information,”[vii] a conclusion he considered to be an insult to his service and suffering. Although he was proud of his time in the Corps, and particularly so of having served honorably for so long as a prisoner, he began to question his value to the Marine Corps. It took another four years for his disability to be rated as permanent. Ferranto permanently retired from the Marine Corps as a Lieutenant Colonel in 1963.

Sometimes referred to as America’s “Forgotten War,” Korea is often overshadowed in American memory by the more high-profile conflicts of World War II and Vietnam. Hidden within this historical haze is the lived experience of prisoners captured in the fighting – the “police action hostages” like Ferranto who fought a war of survival all their own in the physically and psychologically destructive battlegrounds of Korean prison camps. These cigarette papers help recover those stories, for Americans and their United Nations allies. Their narrative power, although anchored to a particular moment in time, also stretches along the entire, remarkable, three-decade career of one Marine, whose assignments took him across continents, through multiple wars, and back home again in service of the Corps and country he loved. Quite the feat for 25 unassuming scraps of aging yellow paper.

[i] 1st Signal Battalion, Historical Diary for November 1950, p. 7. Provided by Korean War Project. Available at: https://www.koreanwar2.org/kwp2/usmc/062/m062_cd20_1950_11_1781.pdf.

[ii] Felix L. Ferranto, Tour of Duty: A Nonfiction Summation, Manuscript, p. 8. From Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division.

[iii] James Angus MacDonald, Jr., The Problem of U.S. Marine Corps Prisoners of War in Korea (Washington, D.C.: History and Museums Division, Headquarters U.S. Marine Corps, 1988), pp. 32-33, 260. Available at: https://www.usmcu.edu/Portals/218/HD/The%20Korean%20War_1950_1953/The%20Problems%20of%20U.S.%20Marine%20Corps%20Prisoners%20of%20War%20in%20Korea%20%20PCN%2019000411200.pdf?ver=2019-04-25-124740-283×tamp=1556211406761.

[iv] Ibid., p. 195.

[v] Ferranto, Tour of Duty, p. 91.

[vi] Ibid., p. 108.

[vii] Ibid., p. 108.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed