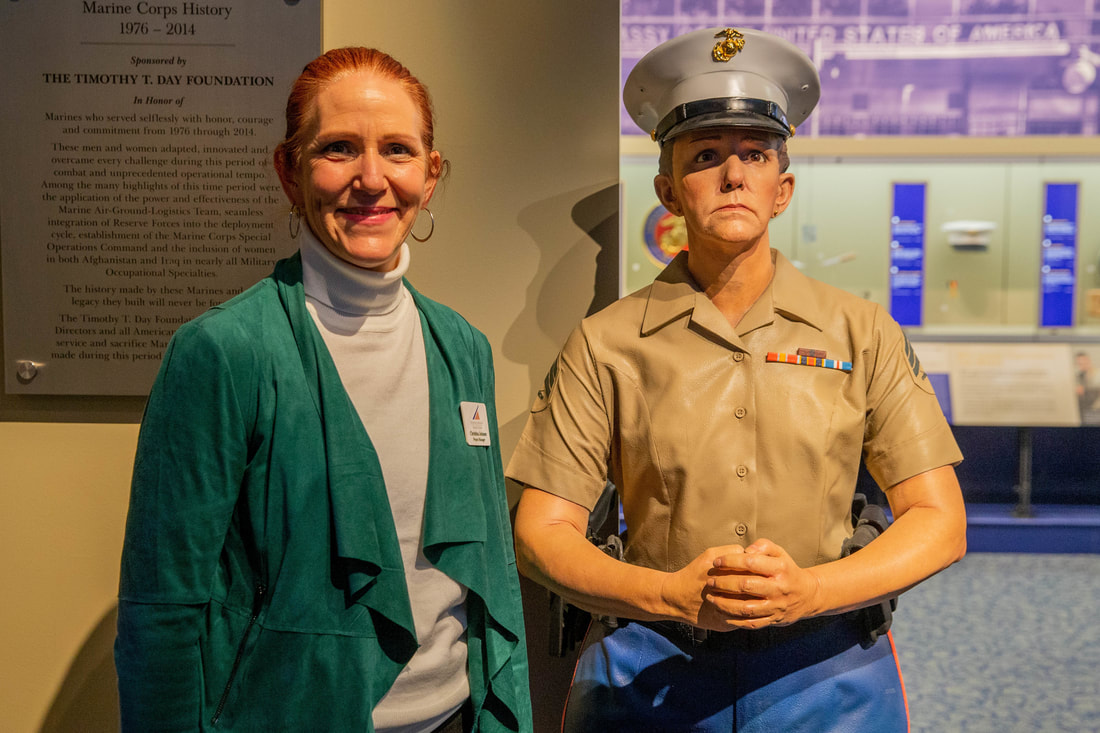

On July 13, 2024, the museum hosted the Heartland Honor Flight of 31 Vietnam veterans to include Medal of Honor recipient Doc Don Ballard. On 16 May 68, while under enemy fire, Doc Ballard was attending to a casualty when an enemy grenade landed near the wounded Marine, four other Marines, and himself. He immediately jumped on the grenade to shield the five Marines from the blast. Realizing that the grenade failed to explode, Doc quickly threw it out of harm's way as it exploded, saving the Marines and himself. Doc then continued to attend to wounded Marines during the firefight. Doc Ballard is pictured with Docent Trish Mangheli.

|

On July 11, 2024, astronaut LtCol Jasmin Moghbeli, USMC spent time answering questions from our Aviation Summer Campers. She is seen here with exhibit specialist Kim Morales. Kim showed her pictures of our astronaut exhibit that Jasmin missed while she was in space.

On July 13, 2024, the museum hosted the Heartland Honor Flight of 31 Vietnam veterans to include Medal of Honor recipient Doc Don Ballard. On 16 May 68, while under enemy fire, Doc Ballard was attending to a casualty when an enemy grenade landed near the wounded Marine, four other Marines, and himself. He immediately jumped on the grenade to shield the five Marines from the blast. Realizing that the grenade failed to explode, Doc quickly threw it out of harm's way as it exploded, saving the Marines and himself. Doc then continued to attend to wounded Marines during the firefight. Doc Ballard is pictured with Docent Trish Mangheli.

1 Comment

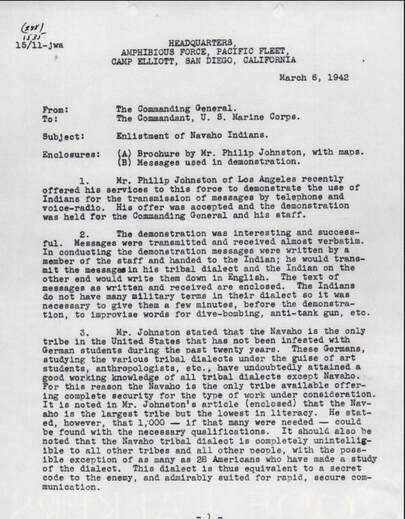

Overview Effective military communications are a vital part of warfighting. An opponent who intercepts critical messages could determine the enemy’s plans, strengths, and weaknesses. During World War II, the execution of amphibious assaults demanded secure and reliable communications between the Marines on the beach and the ships supporting them. Navajo Code Talkers proved indispensable in their ability to send and receive encoded messages quickly and accurately, helping to land and consolidate beachheads. But this was not the only area where Navajo Code Talkers proved themselves. At every level of communications on shipboard, during reconnaissance missions and in the heat of battle on the front lines, Navajo Code Talkers were essential to the Marine operations in the Pacific. Native Americans in the Armed Forces In World War II, approximately 44,000 Native Americans stepped forward and answered the call to serve, with 723 becoming United States Marines; a little more than 400 of them were Navajo Code Talkers. Enduring a long history of violence, dispossession, and the destruction of cultures and languages, Native Americans joined the armed services for varied and complicated reasons. Some were motivated by the desire to carry on traditional ideals of warrior-hood. Others were influenced by western assimilation and pressure to conform to Western ideals, while still others exercised their dual patriotism fighting for both the United States and for their tribal homelands, traditional communities, and their people. The warrior tradition in Native American communities is rooted in the protection of community and land. Although specific traditions vary from tribe to tribe, the basic role of the warrior is one of obligation to his community. Today, Native American veterans continue to hold a special place in their home communities. For the Navajo Nation, the Code Talkers have come to symbolize the spirit of survival, resiliency, and the strength of language and tradition.

Post-World War II Post-war America offered little change for Native Americans. Although U.S. citizenship was granted to Native Americans in 1924, barriers to employ their full rights as citizens existed, and overcoming them remained an uphill battle. The right to vote for all Native Americans was not granted until 1962. Native American veterans who chose to finish high school faced the same federal policies mandating assimilation and prohibiting them from speaking their native languages in the Indian boarding schools. As the Navajo Code Talkers returned home, however, they continued to move forward with their lives. Many participated in traditional ceremonies to cleanse themselves of the war. Other Navajo Marines returned to live quietly in their traditional homeland, or they sought opportunities in new jobs on and off the reservation. A few Code Talkers pursued college and technical degrees through the GI Bill. Many former Navajo Code Talkers became tribal and community leaders. The invaluable contribution made by the Navajo Code Talkers was first recognized in 1969 by the 4th Marine Division Association in Chicago, one year after the declassification of the Navajo code. In 1971, following a gathering of Navajo Code Talkers in Window Rock, Arizona, the capital of the Navajo Nation, the men formed the Navajo Code Talkers Association. Carl Gorman, one of the original first twenty-nine code talkers, designed the official logo. Inspired by a sand painting from a traditional protection ceremony for young men going to war, the symbol he chose represents a “listening device” that warned the Navajo Hero Twins of danger during their journey to visit their father, the Sun. Following a number of local and regional honors and awards, the Navajo Code Talkers finally received national recognition in 1980 with a Presidential Proclamation by Ronald Reagan. In 1981, a commemorative all-Navajo platoon, Platoon 3043, was recruited by the Marine Corps. The following year, the states of Arizona and New Mexico declared a day of honor for the Navajo Code Talkers and introduced a bill to recognize them on a national level. President Reagan declared August 14, 1982, as National Navajo Code Talkers Day. In 2001, the Code Talkers were awarded Congressional Gold and Silver medals for their instrumental role in World War II. BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Books

Young Adult/Children’s Books

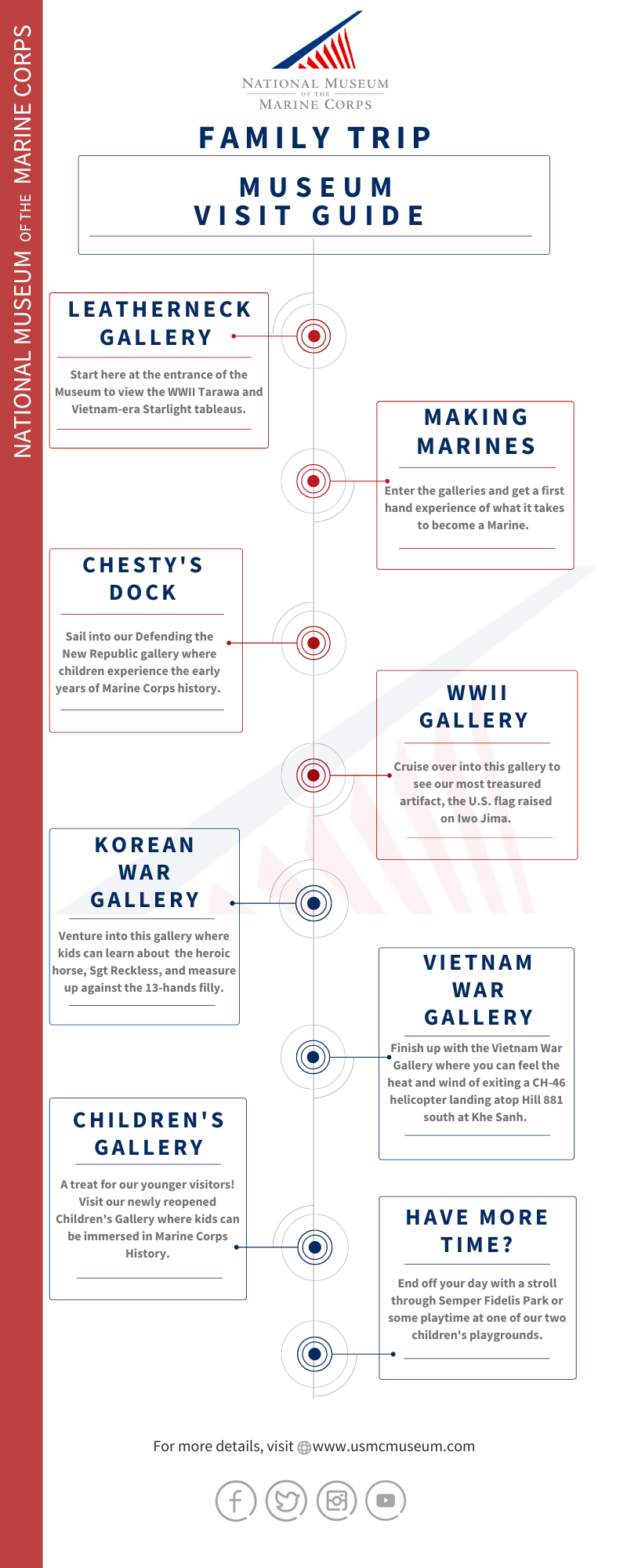

Links of Interest: Navajo Code Talkers: https://navajocodetalkers.org https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/n/code-talkers.html https://americanindian.si.edu/education/codetalkers/html/chapter4.html Planning a trip to the Museum with your family? Here are 8 things at the Museum we think you will enjoy experiencing with your family!

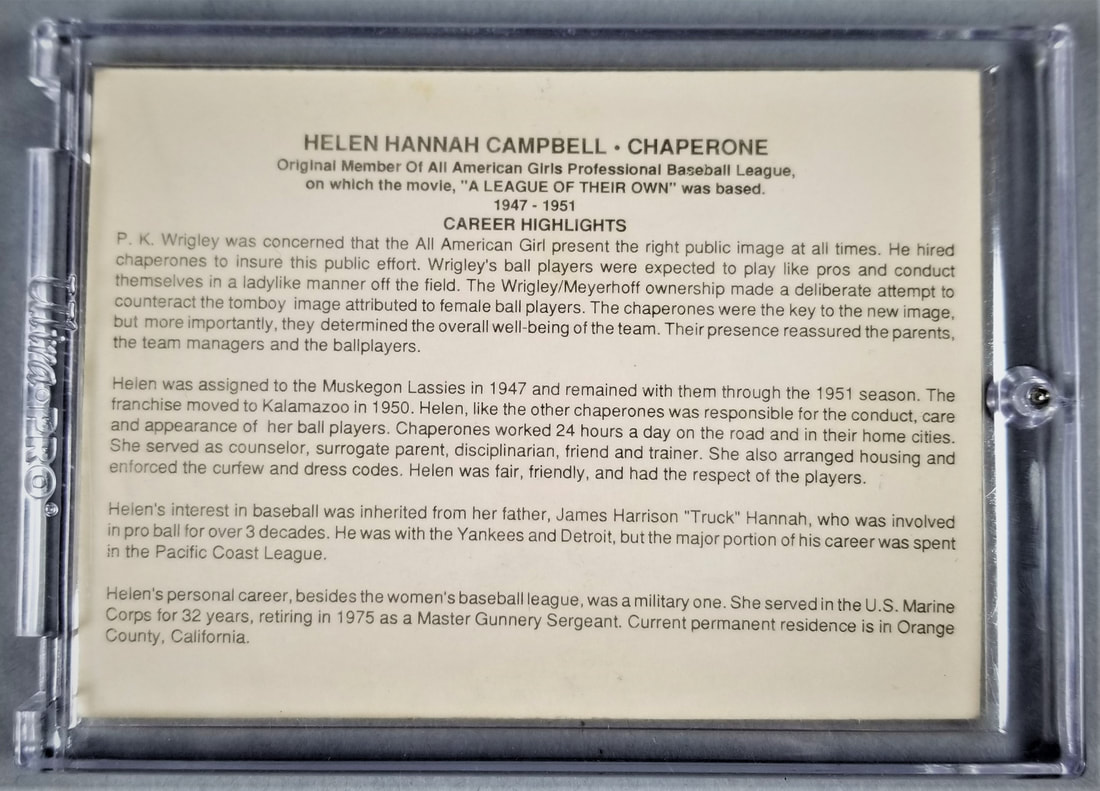

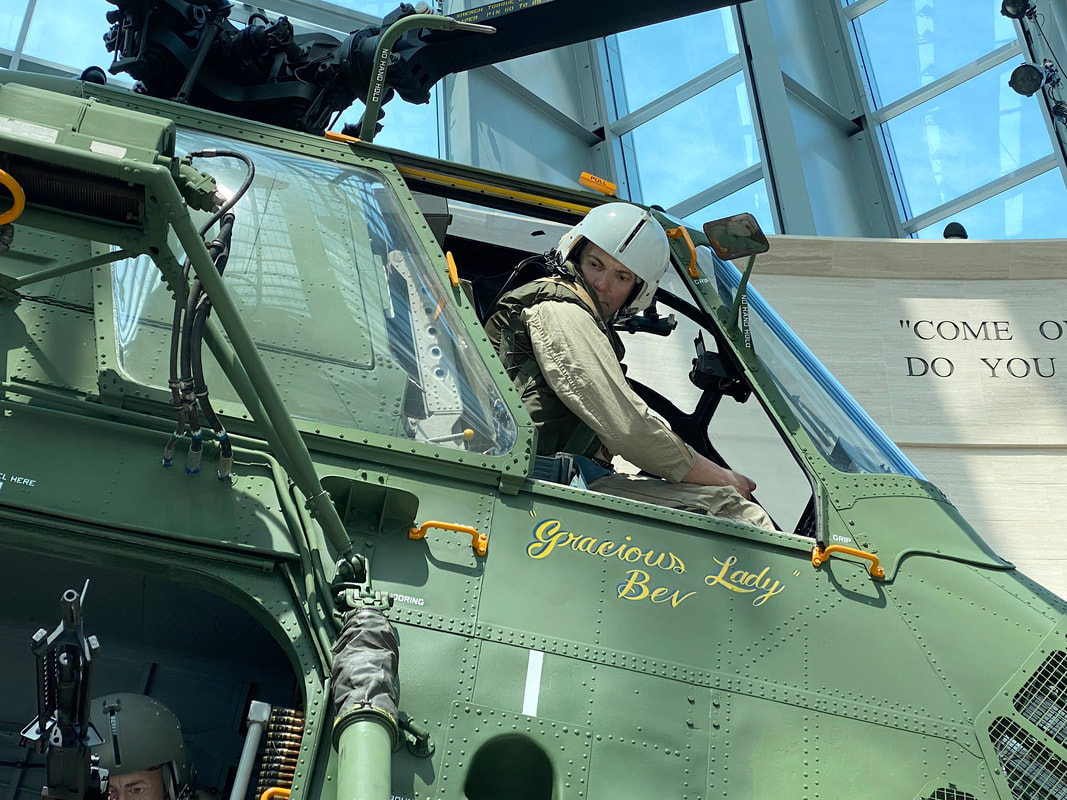

1. Leatherneck Gallery Upon entering the Museum, gaze up and take in the breathtaking view of Leatherneck Gallery. See historical aircraft and a WWII landing craft so close you could almost touch them. 2. Making Marines Next, enter the Making Marines gallery where you’ll get a firsthand experience of what it takes to become a Marine. Here, family members can also test their strength on our pull up bar. 3. Chesty’s Dock Sail on over to the Defending the New Republic gallery where children can enjoy interactive activities at Chesty’s Dock. Learn how to tie seaworthy knots and explore early Marine Corps history. 4. WWII Gallery Take a stroll from early Marine Corps history to the WWII gallery and view our most treasured artifact, the Iwo Jima flag. Also, sit down in our WWII theater and take in a short Bugs Bunny cartoon. 5. Korean War Gallery Next, venture into the Korean War gallery where kids can learn about Sgt Reckless, a decorated war horse, and see how you measure up to the 13 hands mare. 6. Vietnam War Gallery Finish up with the Vietnam War gallery where you can feel the heat and wind upon exiting a real CH-46 helicopter landing atop Hill 881 south at Khe Sanh. 7. Children’s Gallery For the younger visitors, be sure to visit our Children’s Gallery where they can be immersed in Marine Corps history through interactive activities. 8. Semper Fidelis Memorial Park Have extra time? End the day with a stroll through Semper Fidelis Memorial Park or enjoy playtime at the playground. Extra Info: Food Need a break during your visit? The Museum has two restaurants located on the second deck: Devil Dog Diner, a cafeteria-style restaurant, and Tun Tavern, a restaurant fashioned after the legendary tavern where the Corps was founded. Have your own snacks with you? Families are invited to use the picnic tables in the playground area next to the parking lot. (Food and drinks are not allowed in the galleries.) Events Every month the Museum offers family-friendly events such as themed Family Days, Preschool Playdates as well as annual events such as Dog Days at the Museum and a summer concert series. Check out our Calendar of Events for more information. Restrooms All of our restrooms have baby changing tables and oversized accessible stalls. On the first deck, restrooms are located at the entrance and next to the Children's Gallery. On the second deck, we have restrooms near the restaurants, and two family restrooms located in the Medal of Honor lobby. Also on the second deck, there are restrooms and an additional family restroom located in the hallway to the Final Phase galleries overlook. Admission to the Museum is free and events are open to the public. By Jennifer Castro, Cultural & Material History Curator There are few things more American than Marines, baseball, and baseball cards. An artifact in the collection of the National Museum of the Marine Corps encompasses all three. This unique artifact documents the cultural connection between a career Woman Marine and sports – a baseball card of Helen Hannah Campbell, who was a chaperone with the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League from 1947-1951.  Helen Hannah Campbell Helen Hannah Campbell Helen Hannah Campbell enlisted in the Marine Corps on 12 October 1943, initiating a 32-year military career that would span three wars and many duty stations across the United States, from California to Virginia. After training at the Aviation Supply Quartermaster School, she served primarily in administrative capacities. In 1946, at the end of her initial period of enlistment, she joined the Marine Corps Reserves and became involved in baseball. Campbell’s father was professional baseball player James Harrison “Truck” Hannah. His 30-year career included a three-season stint with the New York Yankees from 1918-1920 playing alongside baseball great Babe Ruth. This link to the world of baseball led Campbell in 1947 to become a chaperone in the All-American Girls’ Professional Baseball League (AAGPBL), the organization that inspired the movie A League of Their Own. The AAGPBL was a professional baseball league founded by Philip K. Wrigley in 1943 to prevent the possible collapse of major league baseball parks around the United States while players were serving overseas. After recruiting his players, Wrigley was determined to make them into the ideal “all-American girls.” He emphasized not only the physical training required for the sport, but also training in dress and conduct that would maintain the “squeaky clean” image of the league. Spring training included all-day workouts that were followed by “charm school” in the evenings, where players learned how to put on makeup and how to behave with a date. Players had to adhere to strict “Rules of Conduct.” To ensure they acted like ladies on and off the field, Wrigley hired chaperones for each team. These chaperones traveled with their teams and acted as mothers, nurses, communicators, counselors, disciplinarians, and trainers. Campbell was hired as a chaperone for the Muskegon Lassies and remained with them from 1947-1951. She was on duty 24/7 as she traveled with them, arranging housing, enforcing curfews and dress codes, and ensuring the care and well-being of her players. Campbell left the league in 1951 when she was recalled to active duty during the Korean War. She helped maintain both the woman Marine and AAGPBL legacy by serving on the AAGPBL Historical Society board and her enthusiastic work with the Woman Marines Association. Not only had she joined the Marines to maintain military operations at home when men were needed on the front lines, she also helped preserve America’s favorite pastime.  Helen Hannah Campbell (far right) while a chaperone for the Muskegon Lassies. Helen Hannah Campbell (far right) while a chaperone for the Muskegon Lassies. The baseball card commemorates Campbell’s time in the AAGPBL. She is pictured on the front in her AAGPBL uniform. The reverse provides a brief history of the league, the role of chaperones, and a short biography of Campbell highlighting her career accomplishments. By Larry Burke, NMMC Aviation Curator Most of the aircraft in the National Museum of the Marine Corps (NMMC) have taken a straightforward path on their journey into the collection. They flew for the Marine Corps before being “stricken” from active service because of an accident, coming to the end of the allowed hours of flight time, or simply because the military decided to stop operating that type of aircraft. But the UH-34D on exhibit in the NMMC Leatherneck Gallery took a more circuitous path to the Museum. The aircraft, UH-34D Bureau Number (BuNo) 150570, was delivered to the Marine Corps in October 1963, and was immediately sent to Vietnam where it spent the next six years. Marine Corps practice at the time was to rotate aviation squadrons out of Vietnam after a period, but leave the aircraft in place, to be taken over by the relieving unit. Thus, BuNo 150570 cycled through several squadrons over that period: Marine Medium Helicopter Squadron (HMM)-163 (twice), HMM-361 (three times), HMM-364, HMM-162, HMM-365, HMM-161, HMM-263, HMM-363, and HMM-362. The helicopter finally returned to the United States in June 1969, where it was soon assigned to a Marine Air Reserve Training Division in Atlanta. It spent about two years as a training aircraft before being stricken and sent in early 1972 to Arizona’s Military Aircraft Storage and Disposition Center, now known as the Aerospace Maintenance and Regeneration Group (AMARG) or just the “Boneyard.”  Operation Starlite—UH-34D helicopters from HMM-361 transported 107mm howitzers (a 107mm mortar tube mounted on a pack howitzer chassis) from 3d Battalion, 12th Marines, into position in August 1965. This image was used during the re-painting of BuNo 150570 to determine size and placement of various markings. USMC Photograph. It was later acquired by Orlando Helicopter Airways, a business that purchased and refurbished old military helicopters both for sale and for its own use. Some of the helicopters were even turned into flying RVs! BuNo 150570 was registered with the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to Orlando Helicopter Airways from 1981 to 1994, although registration does not necessarily mean it was flying. It is likely that BuNo 150570 was intended for a remanufacture that never occurred, whether a simple upgrade to turbine engines or a full RV makeover. Orlando Helicopter Airways sold it sometime after its registration lapsed, and by 2000, the airframe was in an aircraft resale yard in Arizona, stripped of its engine and other parts. This is where Marine Helicopter Squadron 361 Veterans Association found it. The Association had formed a few years earlier, its origins in a 1988 USMC Vietnam Helicopter Association reunion. One of the attendees was Alan Weiss who had been a CH-53 crew chief in Vietnam with Marine Heavy Helicopter Squadron HMH-361, the “Flying Tigers.” The unit had first deployed to Vietnam in 1962 as HMM-361 which flew the HUS-1 as the UH-34D was known before the Department of Defense standardized aircraft designations in 1962. During the 1988 reunion, a privately-owned UH-34D flew a demonstration over the crowd. Weiss was among those watching the flight. He took note of the emotional reaction of his fellow veterans, many of whom had worked with or flown in the “Huss” (from its HUS designation) or “Dog” (from the last letter in UH-34D). It was at that point that he decided to purchase and operate a UH-34D as a flying memorial. Weiss assembled a few like-minded veterans who soon formed the Marine Helicopter Squadron 361 Veterans Association to find, acquire, restore to flying condition, and operate a UH-34. In 2000, the Association had raised enough funds to purchase a helicopter. Weiss and three others went to Tucson, Arizona, to look at UH-34s for sale. They looked at over 300 aircraft, all former Army helicopters, before finding a handful of airframes that had served with the Marine Corps. After further research, Weiss identified five that had served with HMM-361. BuNo 150570, though gutted, was in the best shape. The paperwork on the aircraft confirmed its lengthy service with the Marines in Vietnam, including three tours with HMM-361. The Association bought the helicopter and in July 2001, shipped it by truck to Jamesport, New York, to a rented barn used as a restoration hangar. Restoration of the helicopter took more than four years. Alan Weiss recorded over 40,000 hours of volunteer work on the restoration before he stopped keeping track, in addition to more than $350,000 in parts and services, some purchased, some donated. Two volunteers who had dedicated many hours of their time were members of HMM-361 in Vietnam when it was still flying UH-34Ds. In May 2004, a group of HMM-361 veterans calling themselves “Tweed’s Tigers,” held their reunion in Jamesport so they could help with the restoration. The name came from their service in the squadron in Vietnam when it was commanded by LtCol McDonald Tweed (1965-66). The end result of all the time, money, and effort came when the restored BuNo 150570 flew again on 13 November 2005 on its first check flight. It had been painted to reflect its service with HMM-361 during a 1965 deployment to Vietnam, including the ship number, “YN-19,” that it wore at the time. One anachronistic addition was the name “Gracious Lady Bev” in script under the cockpit windows on each side, in honor of Weiss’s wife, Beverly. Weiss had given a lot of his time and money to the restoration and frequently hosted volunteers and others associated with the project in his home. The name on the helicopter was an acknowledgement and gratitude to Beverly for all she had endured during this time. The helicopter made its first public appearance in March 2006. The occasion was a ceremony at MCAS New River, North Carolina, activating Marine Medium Tiltrotor Squadron (VMM)-263. The new squadron had HMM-263 in its lineage; BuNo 150570 had served with that squadron as well. From that point, the Association operated the helicopter as “Freedom’s Flying Memorial,” fulfilling Alan Weiss’s dream of a flying memorial to HMM/HMH-361 and all veterans who flew in Marine helicopters during the Vietnam War. The Association took the helicopter to air shows, reunions, ceremonies, and even veterans’ funerals. At the end of 2008, however, they realized that keeping the aircraft in flying condition and covering operational costs would soon become too much for them to bear; they began a dialogue with the National Museum of the Marine Corps (NMMC) about a possible donation. The Marine Helicopter Squadron 361 Veterans Association decided in 2012 that the tipping point had been reached: operating costs were exceeding what the Association generated in appearance fees, souvenir sales, and donations. Discussions with the NMMC culminated in the helicopter’s final flight on 8 November 2013, its delivery to the Museum. Even after a decade of flight operations, BuNo 150570 was in good condition and the only major restoration work required was to repaint it. While the Association had painted and marked the UH-34D as it would have appeared during one of its tours with HMM-361 in 1965, there were enough cumulative “touch-ups” that the Museum decided it was easier to repaint everything. One thing NMMC staff did not touch were the “Gracious Lady Bev” markings. Though not on the aircraft in 1965, they were left in place as a nod to the restoration work of, and history with, the Marine Helicopter Squadron 361 Veterans Association.  Members of the Marine Helicopter Squadron 361 Veteran's Association gather for a group photo after presenting the Sikorsky UH-34D to the National Museum of the Marine Corps (NMMC), Triangle, Va., Nov. 8, 2013. This helicopter flew numerous medevac and combat missions during the Vietnam War, and will be prepped for display at the NMMC in 2016. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Kathy Reesey/Released) The NMMC installed the UH-34D on exhibit in Leatherneck Gallery, replacing a Korean War-era HRS-1/UH-19 helicopter tableau. This was especially appropriate given that when the HUS/UH-34 came out, it replaced the HRS/UH-19 in Marine squadron service. Since the markings on BuNo 150570 were already period-appropriate to 1965, NMMC staff decided that the new tableau would depict Operation Starlite, which occurred in August of that year. Starlite was significant as the first major offensive of the Vietnam War conducted by an entirely American fighting force. Prior to this, U.S. military forces had merely advised or supported South Vietnamese forces. Starlite represented the “Americanization” of the Vietnam War: using U.S. forces to directly fight the North Vietnam Army and National Liberation Front, the communist insurgent forces in South Vietnam. BuNo 150570 had actually flown in Starlite as part of HMM-361, so the choice of the setting aligned with this helicopter’s history. Swapping out the helicopters was a major effort that needed careful planning. It took time to design the details of the new tableau and assemble the pieces along with period-appropriate uniforms on the cast figures. The new tableau was installed in early 2016. Even then, work was not finished: some markings were not painted on the helicopter until it was lifted into place, time was needed to build the diorama around the aircraft on its stand, and the main and tail rotor blades were not installed until 2017 when nearby temporary walls were removed. Since then, the helicopter has been a significant draw, greeting visitors as they come into the Museum. From its manufacture and delivery to the Marine Corps in 1963, a long career spent carrying Marines in Vietnam, to a private company that might have wanted to make it into a flying RV, to its discovery as a hulk in a dealer’s yard, to its acquisition, restoration, and operation by a group of dedicated veterans, the UH-34D bearing Bureau Number 150570 has had a long and unusual path to becoming a significant exhibit artifact at the National Museum of the Marine Corps.

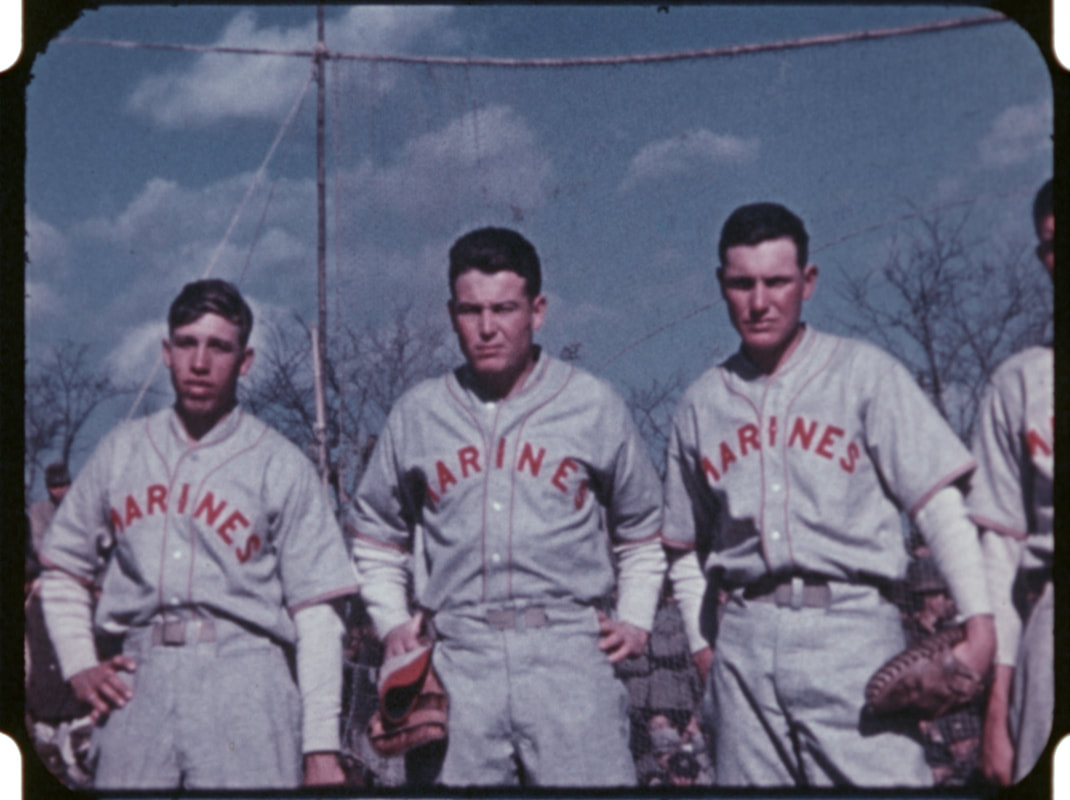

By Kater Miller, NMMC Outreach Curator This article was published in Leatherneck Magazine, December 2021. In the Marine Corps archives, there is film footage of a unique baseball game in which a baseball team composed of U.S. Marines played against a Japanese team in Saga City, Japan. The film itself seems to be the only record of the game. The Marines in the film are from 2nd Battalion, 27th Marine Regiment, 5th Marine Division, which fought across Iwo Jima in February and March 1945. Saga City had been rebombed by the U.S. Army Air Forces on Aug. 5, 1945, though the bombing paled in comparison to those of the larger raids that cities like Tokyo suffered. One of the most striking details about the game is the date that the game was played in occupied Japan: Nov. 4, 1945, just a few months after Japan’s surrender. How could the two groups, both terribly affected by the war, come together as good sportsmen for a lighthearted game of ball? It was not the first or last such baseball game played by U.S. military baseball teams against Japanese teams. In fact, baseball played an important role in the occupation of Japan after World War II ended. Since it was the most popular sport in both countries, the familiar game helped to heal the trauma of both nations reeling from the effects of a devastating and horrific war. The film shows an important aspect of the occupation where the two former combatants participate in a pastime that they both enjoyed without violence or rancor. Japan and the United States share a long history of baseball teams traveling to each other’s countries on good will tours, starting when Waseda University’s team toured the United States in 1905. Marine baseball teams faced Japanese opponents as early as 1910 when Waseda University toured Hawaii and took two out of three games from the Marines. Marines also faced Waseda more than a dozen times in China in the 1920s and 1930s. The 4th Marine Regiment’s baseball team embarked on a successful goodwill tour of Japan in 1930, where they played against college and corporate semi-pro teams. In 1927, Waseda University played the powerful Quantico Marines at Quantico, with Japanese Ambassador Tsuneo Matsudaira and Major General Commandant John A. Lejeune in attendance. The Marines emerged victorious with a score of 9-6, but a July 1927 Leatherneck article indicated that it was due to Waseda’s sloppy baserunning as they outhit the Marines 15-12. WWII impacted baseball in the United States and Japan in different ways. The requirements for manpower by each country’s military strained college and professional sports teams. Young, able-bodied men were needed to serve, and professional baseball leagues in both countries did little to protect their players from service. It was not a foregone conclusion that professional baseball would continue during the war in either country. In the United States, the major leagues, minor leagues and semi-pro leagues did, as did many college baseball teams, with the consent of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, arguing that the entertainment value of baseball was too high and would be good for morale. Baseball did not fare as well in Japan. Pro-war, anti-American factions of the government looked upon baseball suspiciously. The National Professional Baseball League, which formed in 1936, truncated their 1944 season to 35 games, then canceled the 1945 season altogether. College baseball programs met a similar fate. In the minds of many, baseball was a foreign sport that was nearly incompatible with the Japanese culture. In 1942, when the Japanese government restricted the broadcasting of civilian programming to support war mobilization, it meant that no games were broadcast in, even though baseball broadcasts were not the specific target of the move. In contrast, the American military aired games for deployed servicemembers, even if the broadcast was delayed. In the United States, baseball was considered a morale-building venture that helped Americans endure war rationing. Major League Baseball suffered from the war mobilization effort, losing most of their young talent to the draft. The average age of the players of the Major League increased steadily through the war as younger players left the field for military service. By the end of the 1944 season, many critics thought that Major League Baseball would not last another season. However, the league did survive by using players too old or not physically capable of joining the military. While the professional baseball leagues in the United States suffered from talent drain, Americans did not go without baseball. On the contrary, the U.S. military built powerful teams that would have rivaled many of the best baseball teams in history. Military team rosters boasted numerous all-stars, and they traveled the country and abroad playing in exhibition games to enhance the morale of those in service. Baseball exhibition games popped up everywhere there were large numbers of troops. In 1943, even Major League Baseball considered staging regular-season games overseas for the benefit of the troops. In 1944, the U.S. Army suggested a plan for a World Series that pitted service teams against each other as a War Bond sales drive. According to the plan, the best-regarded military teams would play a series of games, some on military bases for the benefit of those in the service, and others in town for civilians. The Army wanted to invite the Navy’s Great Lakes team, the U.S. Army’s 20th Armored Division Team and the Parris Island base team. While this plan was not enacted, it demonstrates that the military thought of creative ways to use the popularity of baseball to support the war effort. In September 1944, the U.S. Navy and U.S. Army put two powerful sides together for the “Servicemen’s World Series.” The series took place in Hawaii and was slated to last seven games, but the series proved so popular that they ended up playing 11 games instead. The Navy walloped the Army, taking the series 8-2-1. The Army invited the Navy to play again the following year, but the Navy had shipped its all-star talent to remote bases in the Pacific to play exhibition games for deployed troops and declined the offer. While much of the nation’s baseball talent coalesced into a few military super teams, the rank and file continued to play baseball too. Commanders encouraged athletics to help keep their Marines in fighting trim, especially when military training had become too grueling. Athletic officers preparing to embark were warned that while some athletic equipment was available in supply depots in the Pacific, it was best to go and purchase softballs, baseballs, gloves, and bats where they were commercially available and take the equipment with them as there was not enough extra equipment in the supply system to go around. On nearly every island in the Pacific, engineers cleared spaces to make baseball diamonds, and intramural service leagues appeared everywhere. When 2nd Bn, 27th Marines of 5th Marine Division deployed from Camp Pendleton, Calif., to Camp Tarawa, Hilo, Hawaii, off-duty Marines participated in athletic leagues, including baseball leagues, at the Kamuela Athletic Field. While on duty, they trained to assault Iwo Jima as part of the V Amphibious Corps. At Iwo Jima, the Marines of the battalion saw some of the most brutal combat of the war. When they were finally pulled off the line, the battle-weary Division was designated to land on Miyako-Jima of the Ryukyu Islands in support of the Okinawa Campaign. Their role in the battle was mercifully called off. The Division was originally slated to recover and train in Guam to prepare for the invasion of the Zhoushan Archipelago off of mainland China. The Marines were elated as they discovered that they would not stop in Guam and instead returned to the familiar Camp Tarawa. The main body of the Division arrived in Hawaii on April 12. The Marines recuperated from their time on Iwo Jima and renamed their baseball field to Iwo Jima Field. They played baseball during the summer of 1945, and their next target changed as well. Instead of assaulting Zhoushan, they prepared to land on Kyushu the southernmost of Japan’s Home Islands, as part of Operation Olympic. Japan’s formal surrender on Sept. 2, 1945, once again changed the Marines’ mission. The Division prepared to occupy Japan. Their mission was to restore order, enforce the terms of the surrender agreement, and assist with the repatriation of the Japanese military. The 2nd Bn, 27th Marines arrived in Japan in late September and were tasked to patrol the area in and around Saga City, the site of the future baseball game. When the 5thMarDiv arrived in Japan, the Division Special Services Office brought athletic equipment with them. Special services personnel built volleyball courts, basketball courts, football fields and baseball fields at every billeting location when possible. They organized inter-unit tournaments, and they estimated that 25 percent of Marines participated in the activities daily. Athletics played an important part in the occupation, both for the occupying forces to enhance the morale and physical fitness of war-weary combat troops waiting to return home, but also as a welcome distraction for the Japanese people, who had experienced extreme privations during the war. Ted De Bary was an interpreter sent to Tokyo and surrounding cities to survey the damage to the area sustained during the war. In a September 1945 letter to a colleague, De Bary wrote about the devastation in the cities that had been subjected to relentless bombardment. De Bary said that the people in these cities almost always steered the conversation to Major League Baseball and the 1945 season’s pennant races. He believed that to the inhabitants of Tokyo, talking about baseball was more desirable than talking about destruction. During the late stages of the war, most baseball stadiums in Japan had been converted to house air defense batteries and as equipment marshaling yards. General Douglas MacArthur prioritized the restoration of the stadiums to playing condition. College baseball returned in October 1945 when the Marines’ familiar opponent, Waseda University, played their archrival, Keio University. Professional baseball returned in November with some exhibition games, and the first full season since the start of the war was played in 1946. On Sept. 22, 1945, a news release by NBC announced an Army baseball team would travel throughout Japan, playing baseball against the Japanese sides, starting with the University of Tokyo. The proceeds from each game were intended to go to war orphans. But the baseball games between American teams and Japanese teams were not necessarily popular. The formal surrender was not even three weeks old. Quite a few American servicemembers did not approve of the effort, thinking it would show how Americans could easily forgive and forget the atrocities committed by the Japanese military during the war. Army Technical Sergeant Howard Hurwitz wrote a letter to Yank magazine showing his disapproval. A poem that went into syndication in the United States mocked the effort. Often, the American public and servicemembers who did not perform occupation duty in Japan held harsher views of their former enemies than the troops that actually went to Japan. Those in Japan had more sympathy for the civilians in the area after having viewed their appalling living conditions. In November 1945 Marines reported that there were no instances where Japanese military members had violated the terms of the surrender. They also reported excellent compliance with American forces, which further elicited feelings of goodwill. The game of Nov. 4, 1945, was not the only game between Americans and the Japanese, but the one thing that makes the footage stand out is that it was filmed in color. Other than the film, very few details of the game are available. None of the Supreme Command Allied Powers reports mention the game, nor do the 5thMarDiv’s War Diaries or command chronologies. The postwar publication, “The Spearhead; the World War II History of the 5th Marine Division” mentions a few games between Marines and locals and states that the locals were pretty good at baseball. Other than that, most of the information about the game comes from this limited piece of ephemera. A short biography of Malcolm “Mel” Waite appeared in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Private First Class Waite served as an automatic rifleman in the battalion. In the biography, he claimed that he played left field during the game, had eight RBIs, and hit for the cycle in the Marines’ 10-5 victory. He went on to play in college as a relief pitcher for the University of Washington from 1947-1951, then played for several years in semi-pro leagues before becoming a high school science teacher. The game carried a carnival-like atmosphere. The lot at which the game was played was named Antonelli Field, after the battalion’s commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel John Antonelli. Rows of uniformed women marched in and participated in running competitions. There was a Kendo and Judo exhibition performed for the Marines, even though the Allied occupation efforts began to curb these activities in an effort to stamp out militarism. There was a group of women in black uniforms playing drums for the audience. Even though the Japanese government took a hostile stance towards baseball, the Saga team had uniforms that were in good order, and so did the Marines. Throngs of civilians showed up to cheer on their team. The filmographer at the game worked to capture the event in excellent detail. He set his camera up in different locations to capture various aspects of the game. He filmed the crowds and the scoreboards and a lot of other little details that add to the beauty of this film. After four years of brutal, terrorizing combat, the former foes got together and played a spirited game. Looking at the game, emotions must have been running high. The Marines wanted to demobilize and go home. The Japanese wanted to put their country back together, but the entertainment-deprived populace relished the opportunity to participate in the day’s festivities and while the Americans took the game with them wherever they went, the Japanese people finally got the game back. It is easy to look at the game as a return to normalcy for both groups of people using the commonly understood universal language of baseball. By the following year, baseball returned for teams at all levels in both countries. Marine Corps Sports Hall of Famers Gil Hodges, Ted Williams, Jerry Coleman and Ted Lyons exchanged their boondockers for spikes and went back to their Major League clubs to continue their illustrious baseball careers, and the era when the U.S. military fielded the best teams in baseball ended. MCA Editor’s note: All photos are still images from video number 162591 from the United States Marine Corps History Division collection at the United States Marine Corps Film Repository at the University of South Carolina. Author: Kater Miller, NMMC Outreach Curator Kater Miller is the outreach curator at the National Museum of the Marine Corps and has been working at the museum for 11 years. He is developing an interpretive plan for the Marine Corps Sports Gallery as part of the Final Phase expansion underway at the museum. He served in the Marine Corps from 2001-2005 as an aviation ordnanceman.  Photo by Lance Cpl. Jennifer Sanchez | Christina Johnson Marine Veteran and Project Manager for the National Museum of the Marine Corps, stands in front of the Marine Corps Embassy Security Guard Section of the museum in Triangle, Va. Johnson's role as project manager is to ensure that the team meets deadline for events and exhibits currently being constructed. (Marine Corps photo by Lance Cpl. Jennifer Sanchez) Marine Corps Base Quantico, VA United States 3.24.2022 Story by Lance Cpl. Jennifer Sanchez Marine Corps Recruiting Command MARINE CORPS BASE QUANTICO, Va. – The saying goes, "Once a Marine, always a Marine". For Christina Johnson, project manager for the National Museum of the Marine Corps, every day reminds her of the faithful service that both she and others have dedicated to the Corps. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Johnson, a former sergeant, stood in the museum overlook while observing the traditional cake cutting ceremony for the Marine Corps Birthday. As the Marines march in with the cake and pass the piece of cake from the oldest Marine to the youngest, Johnson notices a woman next to her crying. "I could tell she was hurting, so I put my hand on her shoulder and tried to comfort her," said Johnson about the proud Marine parent. "Come to find out later; she lost her son recently." After the ceremony, the woman later told Johnson she had a better appreciation for the Marine Corps. The museum provides an avenue for Johnson as she can meet with from different eras and family members, touched by the exhibits of the Marine Corps. "This museum has the ability to bring veterans and families together and become a community for people," said Johnson. "I wouldn't be where I am now if I hadn't joined the Marine Corps." The San Gabriel, Calif., native served in the Marine Corps for five years in the military police occupational specialty and was selected for Marine Corps Embassy Security Guard. After Johnson worked as a contractor in the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration training facility for five years and briefly worked at Prince William Forest Park in Triangle, Va., Johnson jumped at the opportunity to join the NMMC a year after its official opening in 2006. "Over the years, Christina has made a number of contributions that have supported the Museum staff in accomplishing our mission," said Annie Prado, Director of NMMC. "Christina's understanding of the Corps, its ethos and its mission gives her an edge in the work that she does at the Museum." Johnson has become a central figure in creating visual stories for Marine Corps history, even becoming part of an exhibit. She was cast as the figure for the MCESG section in the museum. She is proud of this while working hard to see the museum expansion completed.  Christina Johnson, Marine Veteran and project manager for the National Museum of the Marine Corps, poses with her casting mold figure for the Marine Corps Embassy Security Guard section of the museum in Triangle, Va. Johnson's role as project manager is to ensure that the team meets deadlines for events and exhibits currently being constructed. (Marine Corps photo by Lance Cpl. Jennifer Sanchez) Johnson's role as project manager is to ensure that the team meets deadlines through events or the "Final Phase" of the museum. The final phase is the name of the new exhibit focusing on the continuation of the Marine Corps history and the current structure of the Marines Corps. One of the members Johnson works with is Jennifer Jackson, exhibit specialist, helping with case layouts for the upcoming exhibits. "It's great having her do the planning and the analytical aspect of things for the exhibit," said Jackson. "Christina is very driven, dedicated, even though she's been out for a while, she is a Marine through and through, and I don't think you can take that out of people." Johnson and Jackson have worked on many projects together, but the final phase is an exhibit they are currently excited about showing. With a team of people, they are were able to preserve history soon after it was made in Iraq and Afghanistan for the upcoming exhibit. "When we open up these galleries, we're going to see the Marines and their families come in and it's going to mean so much personally because they were there," said Jackson. Johnson went to Pasadena City College in Pasadena, Calif., after high school. However, after a year in college, she found herself more focused on having a good time than on her studies. "I was just so lost. I went to college, but my heart wasn't in it at all," said Johnson. "I knew that if I stayed, I would have gone down the wrong path. I needed to get my head straight." After one of her classes, she walked across the street to a recruiting office and met with a recruiter, who guided her into the Corps. After a nine-month period in the delayed entry program, she officially stepped onto the yellow footprints at Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island, SC., in February 1993. After graduation, she went to Fort McClellan, Anniston, Ala., for military police school was located and then on to the base provost marshal office at Quantico. Johnson stood 12-hour shifts as a gate watch stander, made patrols on base and guarded the ammunition supply point for her first two years in the Corps. Johnson learned about the MCESG program after a recommendation from her first sergeant. According to MCESG, a security guard's mission is to protect mission personnel and prevent the compromise of national security information and equipment at U.S. facilities. "We used the same weapons and tactics like using pepper spray, handcuffing, restraints and using non-lethal force," said Johnson. "I had to have a clean record, be financially secure and go through psychological and physical tests." At the time, Embassy duty required a Marine to serve overseas for three years with the opportunity to serve in three different embassies, but Johnson had only two years left on her contract. She decided to extend for an extra year in the Marine Corps. Only four of the 80 in her class were women. Women only made up around six percent of the Marine Corps at the time of her service. "[As a woman,] it's always that next part, you have to prove yourself, telling yourself you can do this, I can do this job, this is what I came to do," said Johnson. "In that respect, it was harder to prove to some people than others. They wouldn't exactly talk me down, but I could feel their judgment."  Christina Johnson (left), Marine Veteran and project manager for the National Museum of the Marine Corps, stands next to her fellow Marines during her graduation from the Marine Corps Embassy Security Guard School at Marine Corps Base Quantico, Va. Johnson joined the Marine Corps in 1993 as military police and later on decided to join the MCESG program. (Marine Corps photo by Lance Cpl. Jennifer Sanchez) Johnson completed the school and soon received orders to the U.S. Embassy Branch Office Tel Aviv, Israel. "That was a phenomenal post," said Johnson. "We just went everywhere for professional military education, not only are you learning about their culture but you have the opportunity to be immersed in it." The embassy was right next to the beach, so she would spend time with the locals or with her fellow Marines after the long working hours. Johnson worked 12-hour shifts every day, similar to what she did as military police. She would work three days in a row with two days off; one day in the morning, then middays and lastly ending in evening shifts. "You can spend two weeks in another country and get a taste of it, but in MCESG, you can hang out with the locals and have the opportunity to be invited to their family dinners, weddings and 'bar mitzvahs," Johnson said. Johnson then transferred to U.S. Embassy in Dakar, Senegal. "The people in Senegal were just so unbelievably humble for what they lived in and how they lived," said Johnson. At the time of Johnson's duty in Dakar, military coups were prominent in West Africa. "The people of Senegal gave us a sense of welcoming and they wanted to help in any way they could. They were thankful since there were dangers around the area," said Johnson. "It's not like Dakar's a dangerous post like in other stations you would be confined to compound." Due to continuous strains on her shoulder over the years, Johnson's MCESG career ended early. She had to return to Quantico and went through surgery. Johnson was healing from her operation and could not go back to her life as an MP, therefore she was transferred to the Naval Health Clinic Quantico. It is there that she met her future husband. Now, Johnson takes the knowledge and experiences she gained from the Marine Corps continues to give back long after hanging up the uniform. "Those words that they cram down your throat in boot camp, it instilled that sense of honor and the Esprit de Corps, it sounds so cliché, but it's true," said Johnson. "I have more of a sense of timeliness and that drive now than I did before." Article Source: https://www.dvidshub.net/news/417107/veteran-marine-works-preserve-history-she-helped-create Visitors to the Museum can view Christina Johnson's cast figure in the "No Better Friend" exhibit in Legacy Walk.

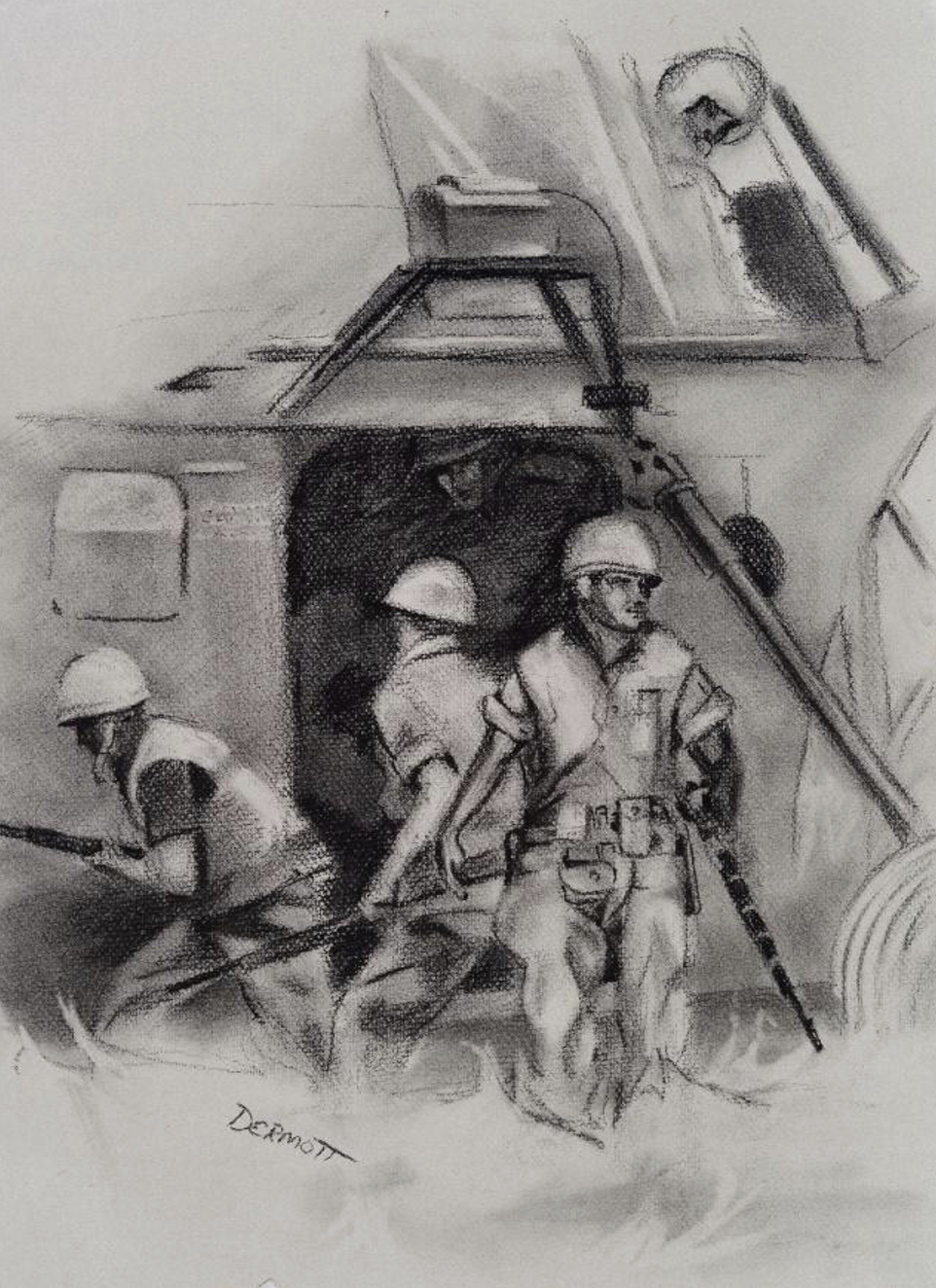

WASHINGTON, DC, UNITED STATES 02.03.2022 Story by Petty Officer 1st Class Abigayle Lutz Naval History and Heritage Command Naval History and Heritage Command's (NHHC) Underwater Archeology Branch completed the conservation of a World War II artifact, an M1 Garand rifle, Feb. 3. In 2016, the National Museum of the Marine Corps (NMMC) began collaborations with NHHC's Underwater Archeology Branch to assist with the artifact's conservation. NHHC's conservation team utilized their skills and resources to save the artifact from further deterioration. "The M1 Garand is quite a unique object," said Shanna Daniel, Lead Archaeological Conservator at NHHC. "When it first came into our laboratory, we were doing an assessment of it, and we started realizing different aspects that we didn't see before." U.S. Marines used the M1 Garand during the World War II battle against Japanese military forces on Makin Island. For over 50 years, the artifact was submerged in a marine environment before its recovery in 1999. By Joan Thomas, NMMC Art CuratorOperation Independence took place in Quang Nam Province, South Vietnam, in February 1967. The action involved two battalions of the 9th Marines, 3d Marine Division. This was one of several operations that took place in late January and early February of 1967. 1stLt Leonard Dermott, USMCR documented the operation for the Marine Corps Combat Art Program. He was among the first Marines selected to serve as a combat artist in Vietnam. Initially, the combat art studio was going to be in Japan with the artists making trips to and from Vietnam to document the actions of the Marines. Dermott recommended finding a studio in Vietnam so the artists would not lose time and mobility by being so far away from the action. They would attend briefings and be able to move quickly to embed for several days, or for the duration of an operation, to record the experience. This was successful, with a studio set up at the Combat Information Bureau in Da Nang. Dermott and the other active duty artists were able to manage the activities of the reservists and civilian artists who came for several weeks at a time to document Marine Corps actions. During his time in Vietnam, Dermott covered a wide range of topics from everyday experiences, the wounded, patrols, and combat operations. The drawings below are Dermott’s impressions of the combat he witnessed and participated in during Operation Independence. While Dermott was adept in working with watercolors and oils, when he was in the field, he worked in pencil, charcoal, and felt tip pens to be able to quickly document the events around him. In all, Dermott produced more than 180 works of art for the Marine Corps collection. Further reading is available in the U.S. Marine Corps History Division publication Marines in Vietnam 1954-1973: An Anthology and Annotated Bibliography, 1985. This publication can be downloaded here. The Marine Corps Combat Art Program traces its origins to 1942. Its mission: Keep Americans informed about what “their Marines” are doing at home and overseas. Managed today by the National Museum of the Marine Corps, the collection has grown to include more than 9,000 works of art created by 350 artists.

Want to learn more about the Combat Art Program? Join our Facebook Group and follow us on Instagram.  Donated by Mrs. Clara Wietrzak 2005.125.38 Donated by Mrs. Clara Wietrzak 2005.125.38 By Jennifer L. Castro, NMMC Cultural & Material History Curator The U.S. military has traditionally shied away from incorporating darker images of heraldry into its patches and insignia. The main exception, however, are the World War II Marine Raiders and their use of the skull. Col Evans Carlson’s 2d Raider Battalion first used an unofficial skull with crossed cutlasses as its unofficial battalion logo and calling card. It was influential in the adaption of the Marine Raider Regiment shoulder patch. The design is still used in various ways by Marines in the U.S. Special Operations Command (MARSOC) today. Other, lesser known units have also appropriated skulls for their unofficial unit insignia. In the Halloween spirit of their darker heraldry, the following are artifacts from the Museum’s collection that feature skulls in their design. World War II Raider Battalion Member Ring This ring belonged to PFC Ted Dougherty, a former member of the 1st Raider Battalion. When the Raider Regiment disbanded in early 1944, Dougherty transferred to the newly formed 2d Battalion, 27th Regiment, which was part of the 5th Marine Division and fought in the Battle of Iwo Jima. The skull and crossbones on the face of this ring reference the design of the Marine Raider Regiment patch insignia. The design was later adopted into insignia for MARSOC, activated 20 June 2003, and is still used today! |

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

We are always happy to hear from you Get in touch

National Museum of the Marine Corps

1775 Semper Fidelis Way Triangle, VA 22172 Toll Free: 1.877.653.1775 |

VISIT

RESEARCH |

LINKS

|

JOIN US ONLINE!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed