From Devil Dogs to Pluto the Pup: World War II Marine Corps Aviation Insignia

by Allison Ramsey

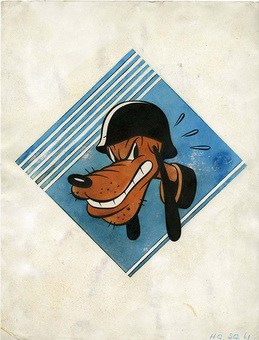

Walt Disney Studios, HQSQ-61, Ink & Watercolor, 14 x 10.5 in. From: National Museum of the Marine Corps, Triangle, Virginia. NMMC Accession Number 2014.96.28

Walt Disney Studios, HQSQ-61, Ink & Watercolor, 14 x 10.5 in. From: National Museum of the Marine Corps, Triangle, Virginia. NMMC Accession Number 2014.96.28

As an intern at the National Museum of the Marine Corps during the spring of 2014, I discovered how to convince the curators to drop what they were doing and come and look at an artifact, or in my case, a group of artifacts. The day had started out normally enough: one of the Museum’s collections storage buildings was scheduled to receive some new storage shelves, which required an inventory and a temporary home for some items while the switch in storage units was made. Thoroughly prepared for a morning of moving photographs and maps, a volunteer and I began our work, moving methodically from bottom to top of the large flat file drawers. However, once we reached the top two drawers, well above my 5’4” height, we found something entirely different.

Tucked away in the very top of the flat files, we discovered a treasure trove of artwork. One after another, illustration board after illustration board came out, some with very familiar characters and bearing very recognizable artist signatures. Here, a black sheep and stars in casein paint; there, a screen print of Bugs Bunny, ready for a boxing match. Further on an unmistakable Walt Disney signature. I could tell this day was not going to be as routine as I had expected. Within the next 20 minutes, a large conference table was covered with artwork dating from World War II, and the Museum’s curators dropped what they were doing to take a look at the new discovery.

This day marked the beginning of an exciting project that lasted the entire summer. Nearly 150 pieces of original World War II-era artwork depicting Marine Corps aviation squadrons had been discovered, and the pieces needed to be researched, accessioned, cataloged, and scanned. Mediums varied from conté crayon and graphite to watercolors and gouache paint. The origin of the collection remains murky. There is no record of the artwork being donated or transferred to the Museum. However, it is clear that most of the works had been submitted for a National Geographic special edition magazine in 1944 that highlighted insignia artwork produced during the war years. Many bear a stamp dated 1944 that cleared them for publication, and a small paper taped on the back states that the artwork was sent to the magazine. These indicators helped to authenticate the pieces as originals

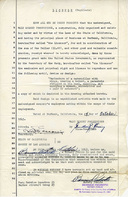

Additionally, a great deal of primary source information on these artifacts was available in the Museum’s research library. Original and carbon copies of memoranda and license agreements helped to map out the approval process to formally establish squadron insignia, and these original paintings were a crucial part of that process. In order to receive approval from the wartime Department of the Navy, certain criteria needed to be met in the form of “enclosures,” to include the original artwork, several photographs of the design, a detailed explanation of the colors used, and a discussion of the significance of the concept being depicted. A 1944 memo regarding squadron insignia requested, for example, “that a colored drawing of the insignia, approximately 11” x 14”, suitable for framing, and twelve 8” x 10” glossy photographic prints thereof, be forwarded to CNO [Chief of Naval Operations] for display and filing purposes. It is also requested that a brief outline of the significance of the motif accompany these prints.” Meanwhile, an Aviation Circular Letter from the CNO in 1944 outlined design standards by asserting that, “(1) The design shall be in keeping with the dignity of the service; (2) The motif shall have originality; (3) Significance shall portray generally the mission of the activity and be of such scope that the design is appropriate for succeeding activities of same mission.”

Tucked away in the very top of the flat files, we discovered a treasure trove of artwork. One after another, illustration board after illustration board came out, some with very familiar characters and bearing very recognizable artist signatures. Here, a black sheep and stars in casein paint; there, a screen print of Bugs Bunny, ready for a boxing match. Further on an unmistakable Walt Disney signature. I could tell this day was not going to be as routine as I had expected. Within the next 20 minutes, a large conference table was covered with artwork dating from World War II, and the Museum’s curators dropped what they were doing to take a look at the new discovery.

This day marked the beginning of an exciting project that lasted the entire summer. Nearly 150 pieces of original World War II-era artwork depicting Marine Corps aviation squadrons had been discovered, and the pieces needed to be researched, accessioned, cataloged, and scanned. Mediums varied from conté crayon and graphite to watercolors and gouache paint. The origin of the collection remains murky. There is no record of the artwork being donated or transferred to the Museum. However, it is clear that most of the works had been submitted for a National Geographic special edition magazine in 1944 that highlighted insignia artwork produced during the war years. Many bear a stamp dated 1944 that cleared them for publication, and a small paper taped on the back states that the artwork was sent to the magazine. These indicators helped to authenticate the pieces as originals

Additionally, a great deal of primary source information on these artifacts was available in the Museum’s research library. Original and carbon copies of memoranda and license agreements helped to map out the approval process to formally establish squadron insignia, and these original paintings were a crucial part of that process. In order to receive approval from the wartime Department of the Navy, certain criteria needed to be met in the form of “enclosures,” to include the original artwork, several photographs of the design, a detailed explanation of the colors used, and a discussion of the significance of the concept being depicted. A 1944 memo regarding squadron insignia requested, for example, “that a colored drawing of the insignia, approximately 11” x 14”, suitable for framing, and twelve 8” x 10” glossy photographic prints thereof, be forwarded to CNO [Chief of Naval Operations] for display and filing purposes. It is also requested that a brief outline of the significance of the motif accompany these prints.” Meanwhile, an Aviation Circular Letter from the CNO in 1944 outlined design standards by asserting that, “(1) The design shall be in keeping with the dignity of the service; (2) The motif shall have originality; (3) Significance shall portray generally the mission of the activity and be of such scope that the design is appropriate for succeeding activities of same mission.”

|

“An example of significance and its importance in the approval process can be seen in the case of Marine Air Group 25’s interesting and slightly confusing insigne sporting a boxcar with wings and Latin motto underneath. The design makes perfect sense once the significance is explained:

Securité en Nuages (Security in Clouds) has proven a worthy motto and a necessity when flying in the enemy zone with no armament other than personal sidearms. The flying boxcar is representative of the size and cargo capacity of R4D type aircraft. The red cross is very significant in that this Group has evacuated several thousand war casualties from the Guadalcanal-Solomon area under extremely hazardous conditions.” |

|

Request for new designs followed the chain of command, starting at the commanding officer of the squadron up to the Chief of Naval Operations via the commanding generals of the aircraft wing, the fleet, and the Commandant of the Marine Corps. After the request was submitted, suggestions for changes could be considered. These included directions to omit identifiers, such as a squadron number, or technical aircraft designs that might aid the enemy. Several squadron artwork pieces in the Museum’s collection have squadron names in bold letter across the top or bottom in ink, but struck through in pencil with the word “omit” in the margins. In these cases, modified versions of the design were requested. After acceptance, the design required a trend of endorsement memos from the Chain and a signed and notarized license agreement if an outside production company had created the work.

The artists represented in the collection came from many different places and backgrounds. Paul Arlt put his artistic abilities to use while serving in Marine Scout Bombing Squadron 241 (VMSB-241) as a Marine Corps combat artist. While on duty, he created an insignia for his squadron. The original idea for this design came from Lt Wallace P. Wyatt, but the smooth, simple lines and lettering are recognizable as belonging to Arlt. The insignia shows a black devil standing atop a white cloud “awaiting the moment to hurl a high explosive charge screaming from the heavens to smash into the ranks of an infamous enemy crouched below.” The Latin phrase “Alere Flammam” means “to feed the flame,” which, according to the original insignia significance memorandum, was symbolic of an intent to feed the flame started by the enemy until they themselves were consumed “by the heat of an outraged nation.” |

Companies like Walt Disney Productions contributed to the creation of Marine Corps insignia as well. By 1944 at least 80% of the Disney company’s work focused on assisting the war effort in lieu of its regular production activities. The studio designed around 1,200 insignia for everything from bombing squadrons to chaplain corps, incorporating favorite characters like Donald Duck, Goofy, and Dumbo. In some instances, the designs included new characters to add a personalized touch that represented the unit’s duties and location. The license agreements for insignia designs coming from Walt Disney Productions demonstrate Disney’s willingness to help with the war effort: the United States Government was granted “The exclusive and perpetual right and license to produce the designs...for and in consideration of the sum of One Dollar (1.00).”

|

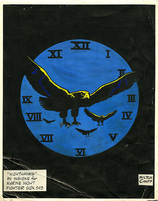

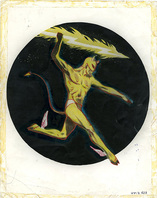

Milton Caniff, a prolific and popular cartoonist, worked on his own projects to support military personnel overseas. He showed his support by furnishing art for the armed forces, to include the Army’s “ Pocket Guide to China” and a weekly cartoon strip titled Male Call, which was distributed to over a thousand Army newspapers, along with a couple dozen Navy and Marine Corps publications, too. He also provided designs for Marine Corps Aviation insignia. The 1944 Marine Night Fighter Squadron543 (VMFN-543) Nighthawks insignia, featuring four hawks in flight through a night sky, and Marine Bombing Squadron 623’s (VMB-623) insignia, displaying a character with winged feet, horns, and devil tail, exhibit high contrasts in shading that create a cinematic effect — classic examples of Caniff’s design style.

|

|

From artist to artist, there are some common themes to the insignia designs. As one might expect, a large number of avian figures were featured: buzzards, pelicans, turkeys, hawks, and crows have all made appearances. Marine Fighting Squadron 313 (VMF-313) was nicknamed the “Lily Packin’ Hellbirds.” Lt William Long’s design featured a bird that suggested “the lightning which our ships carry. This blood-red, lethal demon, spitting his deadly message also has the finesse to bestow upon his victims that lovely symbol of eternal sleep, ‘the lily’.” The importance of flight was represented by a bird, supplemented with a lethal color, along with a flower symbol to represent death.

Squadrons often added stars to their designs as an alternative way to show their squadron number as well. Marine Night Fighting Squadron531’s (VMFN-531) insignia provides a good example of this. The stars are purposely arranged in a group of five, followed by a group of three, and finally a lone star on the right. Stars could also be used to commemorate past achievements. In Marine Fighting Squadron 213’s insignia, the nine stars “indicate the nine aces who distinguished themselves during their first tour of duty overseas with VMF-213.” The hawk also figured symbolically into the design, signifying strength, ferocity, and “superior flying ability anywhere on the land & sea.” |

|

The discovery of this collection of insignia provides an opportunity to study Marine Corps aviation in a new light. The growth of aviation units and squadrons during World War II led to new squadrons being established and new insignia to go with them. Many interesting designs were created through an approval process that required originality in motif and significance unique to the squadron. The art was crafted by a variety of creative people, ranging from commanding officers, combat artists, and military spouses to well-known cartoonists and illustrators like Walt Disney, Leon Schlesinger, and Milton Caniff. Through various characters, colors, and designs, the artwork tells the story of the Marines and the squadrons’ missions, capabilities, and characteristics. The development of esprit de corps for Marines within the squadrons through art and a growing network of civilians who also contributed their time and talent into the creation of artwork provide an interesting and unique perspective of World War II Marine Corps Aviation.

|

Allison Ramsey was a Special Assistant at the National Museum of the Marine Corps. She graduated Cum Laude with a BA in History from American Military University and is currently enrolled in the Museum Studies Advanced Academic Program at Johns Hopkins University.

|

|

We are always happy to hear from you Get in touch

THE MUSEUM IS OPEN! PLAN YOUR VISIT HERE.

National Museum of the Marine Corps

1775 Semper Fidelis Way Triangle, VA 22172 Toll Free: 1.877.653.1775 |

VISIT

RESEARCH |

LINKS

|

JOIN US ONLINE!

|

©

Copyright 2021. Admission to the National Museum of the Marine Corps is FREE. Hours are 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM every day except Christmas Day.