The Story of a WWII Identification Bracelet: Major L.D. Everton

In Annandale, Virginia, during the early 1990s, Mrs. Ellen Littlefield was working in the rose garden of her home. Something unusual caught her eye while she was sifting through the soft soil. She was surprised to discover a slightly worn bracelet buried in the ground. Upon closer inspection, she noticed the front of the band had a small U.S. Marine Corps "Eagle, Globe, and Anchor" emblem. It was also engraved:

MAJOR L. D.EVERTON

U*S*M*C

The underside of the bracelet was ornately inscribed:

TYPE-0- T 9/41

DALE from Delores

1/8 GF 10K LGB

The bracelet obviously belonged to a Marine officer, but who was L. D. Everton? When did he serve, and what did these markings mean? Amazed by their discovery, Ellen and her husband, Dr. Keith Littlefield, attempted for years to identify the owner and locate surviving family members without success.

In the spring of 2014, the Littlefields attended an artifact roadshow hosted by the Stafford County (Virginia) Museum and Cultural Center. From ads in the paper, the couple learned that a military specialist from the National Museum of the Marine Corps was assisting at the event. They hoped that the Marine Corps could help solve their mystery. The Littlefields wondered if it was possible to discover who Major L. D. Everton was and if the Museum might be able to locate surviving members of the family.

|

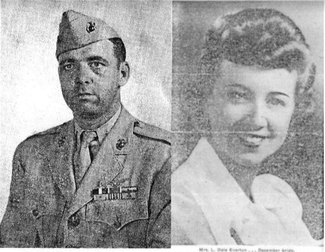

Through historical research, genealogical resources, and official U.S. Marine Corps unit muster rolls, curators at the National Museum of the Marine Corps were able to conclusively identify the owner of the bracelet. He was Major Loren Dale Everton, a decorated Marine aviator, fighter ace, and husband to Mrs. Delores Everton. Perhaps even more surprising, research also showed that the Marine pilot’s younger brother, Mr. Keith Everton, still survived. The curators contacted this relative, who provided significant biographical details and photos relating to the history of Major L. D. Everton. The relative also expressed his desire that the artifact remain with the Museum. The Littlefields happily agreed to donate the relic with the Everton family’s consent. |

L. D . Everton Biography

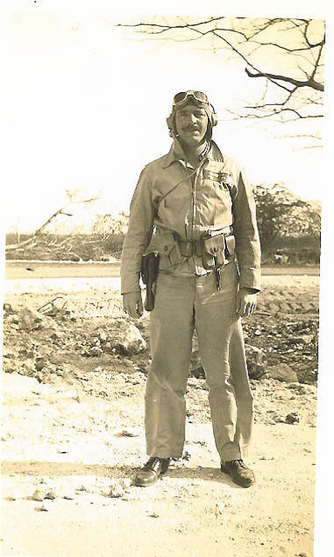

Loren Dale Everton entered the University of Nebraska, College of Pharmacy, in 1933. There, he excelled at his studies, became a registered pharmacist, and received four years of ROTC training. Upon graduation in 1937, he was commissioned in the U.S. Army Reserve. However, Everton loved to fly, having earned his license at age 17. He resigned his commission to enter flight training in the United States Marine Corps at Pensacola, Florida, in 1939[1]. Known to his fellow fliers as “Doc” Everton (due to his status as a pharmacist), he was trained as a dive-bomber and deployed during World War II to Midway Island. There, on 7 December 1941, when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, he flew in defense operations[2]. Ordered to Hawaii, Everton was assigned to VMF-212 but temporarily transferred to VMF-223 (when the squadron required more experienced pilots) for the opening air battles for Guadalcanal in August 1942[3]. Everton was among the first pilots who landed on the island and was happily greeted by the beleaguered Marines on the ground.[4] The Battle of Guadalcanal was one of the most grueling actions of the war, and the airmen who comprised the hastily assembled “Cactus Air Force” played a vital part in the decisive outcome. They did this despite brutal attrition among some of the worst prolonged conditions faced by any American aviators during the war.[5]

For his heroic actions during the battle, Everton received the Navy Cross, the second highest valor decoration awarded to U.S. Marines. His citation reads: [Major Loren Dale Everton] …awarded the Navy Cross for extraordinary heroism and distinguished service in the line of his profession while serving as a Pilot in Marine Fighting Squadron TWO HUNDRED TWELVE (VMF-212), Marine Air Group TWENTY-THREE (MAG-23), FIRST Marine Aircraft Wing, in aerial combat with enemy Japanese forces over Guadalcanal, in the Solomon Islands during August and October 1942. Throughout that strenuous period when the island airfield was under constant bombardment and our precarious ground positions were menaced by the desperate counter thrusts of a fanatical foe, Captain Everton repeatedly patrolled hostile territory, strafed enemy ships and intercepted persistent bombing flights. With bold determination and courageous disregard of personal safety, he pressed home numerous attacks against heavily escorted waves of invading bombers and, in three vigorous fights against tremendous odds, shot down a total of seven Japanese planes. His superb flying skill and dauntless initiative were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.[6] |

Major Everton would also receive the Distinguished Flying Cross for the same period.[7] On 20 October 1942, however, his luck would run out. During yet another chaotic air battle, “Doc” skillfully positioned his aircraft behind a fleeing Japanese fighter when another Zero suddenly ambushed him from the rear. The Japanese fighter riddled his F4F-4 Wildcat with machine gun bullets and 20mm cannon fire. The shells exploded in the cockpit, wounded Everton in the leg, and knocked him from the controls. Everton later recounted that he let the aircraft spiral about 19,000 feet in an effort to “play dead” before recovering his aircraft to make an emergency forced landing.[8]

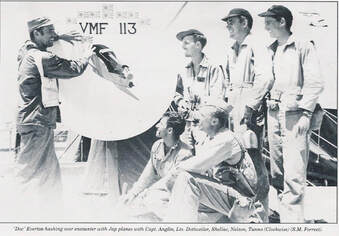

Everton was evacuated from the island shortly thereafter. He was awarded the Purple Heart, and, after recovering from his wounds, he became the Commanding Officer of VMF-113 in January 1943. “Doc” Everton then led the squadron in the assault on the Marshall Islands.[9] There, he downed an additional two enemy fighters (with an additional probable kill). With this accomplishment, Everton achieved the rare and notable status as a Marine “Double Ace,” officially credited with the destruction of 12 enemy aircraft during the war.[10]

Following World War II, Major Everton became the commanding officer of VMF-122 and led a jet fighter demonstration team similar to the U.S. Navy’s Blue Angels[11]. During the 1950s, he was promoted to colonel and served in a number of training commands and headquarters staffs, which included a lengthy period as the executive officer of the intelligence division, Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, D.C., until 1958. From 1962 to 1964, Col Everton was the commanding officer of Marine Barracks, Bremerton, Washington.[12]

Artifact History

While the museum confirmed who “Doc” Everton was, how his bracelet came to be found in Annandale, Virginia, is still unknown. Research of property records for Annandale do not indicate that the Evertons ever owned the home where his bracelet was discovered. The house, built in 1948, was possibly rented to military and other Washington-based families during the late 1950s. This would match the approximate time in which Col Everton was assigned to Headquarters Marine Corps at the Pentagon in Northern Virginia. It is also possible that he lived there during the mid-to-late-1960s, when Everton was believed to have returned to the area as a civilian consultant to the Pentagon.

As an artifact, this World War II era identification bracelet is unique, both as a token of affection from Delores Everton to her husband and as an important form of military personal identification. The engravings contain the same information typically seen on WWII-era U.S. Marine identification tags, with Everton’s blood type “O” marked prominently on the reverse. Additionally, the aviator’s tetanus toxoid inoculation date, known as a “T-number,” is stamped in the form of T 9/41 (September 1941). The bracelet is also manufacturer-marked LGB, representing the jewelry maker L.G. Balfour Company, a major supplier of wartime jewelry during the 1940s.

Identification bracelets such as this were popular items during the Second World War. Often presented to service members by loved ones, they also served a practical purpose, particularly in the Pacific theater. When identification tags were first issued by the U.S. Marine Corps in 1917, they were secured to the wearer by necklaces of woven thin Monel wire, cloth tape, or even improvised bootlaces. These crude necklaces often failed in the harsh climates of the Pacific theater. As a result, tags were often lost in training and combat. When service members were able to obtain identification devices like Everton’s bracelet, they were ensured an added degree of protection if wounded or killed in action. It was both a loving and practical gift.

National Museum of the Marine Corps Artifact: 2014.XX.1 Bracelet, Identification

Colonel Loren Dale “Doc” Everton retired from the United States Marine Corps on 39 June 1967. He was married to his wife, Delores Everton, for 48 years and passed away in February 1991. His identification bracelet was accepted into the permanent collection of the National Museum of the Marine Corps in September 2014. Assigned the accession number 2014.XX.1, it was donated by Ellen Littlefield in memory of Colonel L. D. “Doc” Everton USMC (Ret.).

[1] “With Uncle Sam: Marine of Crofton Led Plane Research,” Nebraska Mortar & Pestle, December 1944.

[2] Colonel J. Ward Boyce, Editor, American Fighter Aces Album (Mesa, Arizona: The American Fighter Aces Association, 1996), p 260.

[3] John B. Lundstrom, The First Team and the Guadalcanal Campaign: Naval Fighter Combat from August to November 1942 (Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 1994), pp 29-31.

[4] Stephen Sherman, “Marine Corps Aces of WWII.” accessed 3/10/2014 http://acepilots.com/usmc_aces.html.

[5] Richard B. Frank, Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle (New York, NY: Penguin Books, 1990), pp 209-210.

[6] Official Navy Cross Citation, U.S. Marine Corps: General Orders, Board of Awards: December 22, 1948.

[7] Jane Blakeney, Heroes of US Marine Corps 1861-1955.

[8] Sherman, “Marine Corps Aces of WWII.”

[9] Congressional Record, 102d Congress, Tribute to Colonel L.D. “Doc” Everton, February 28, 1991.

[10] Frank Olynyk, Stars & Bars: A Tribute to the American Fighter Ace 1920-1973 (Grub Street, 1995), Everton Bio. (Author Note: Everton possibly shot down 13 total aircraft, but the probable kill leaves this number in flux.)

[11] “Deliver First F2H-2 to Marines,” McDonnell Airscoop (McDonnell Aircraft Corp., Lambert Field, St. Louis, MO), January 1950.

[12] Personnel Records: Loren Dale Everton, U.S. Marine Corps Muster Rolls 1798-1958.

While the museum confirmed who “Doc” Everton was, how his bracelet came to be found in Annandale, Virginia, is still unknown. Research of property records for Annandale do not indicate that the Evertons ever owned the home where his bracelet was discovered. The house, built in 1948, was possibly rented to military and other Washington-based families during the late 1950s. This would match the approximate time in which Col Everton was assigned to Headquarters Marine Corps at the Pentagon in Northern Virginia. It is also possible that he lived there during the mid-to-late-1960s, when Everton was believed to have returned to the area as a civilian consultant to the Pentagon.

As an artifact, this World War II era identification bracelet is unique, both as a token of affection from Delores Everton to her husband and as an important form of military personal identification. The engravings contain the same information typically seen on WWII-era U.S. Marine identification tags, with Everton’s blood type “O” marked prominently on the reverse. Additionally, the aviator’s tetanus toxoid inoculation date, known as a “T-number,” is stamped in the form of T 9/41 (September 1941). The bracelet is also manufacturer-marked LGB, representing the jewelry maker L.G. Balfour Company, a major supplier of wartime jewelry during the 1940s.

Identification bracelets such as this were popular items during the Second World War. Often presented to service members by loved ones, they also served a practical purpose, particularly in the Pacific theater. When identification tags were first issued by the U.S. Marine Corps in 1917, they were secured to the wearer by necklaces of woven thin Monel wire, cloth tape, or even improvised bootlaces. These crude necklaces often failed in the harsh climates of the Pacific theater. As a result, tags were often lost in training and combat. When service members were able to obtain identification devices like Everton’s bracelet, they were ensured an added degree of protection if wounded or killed in action. It was both a loving and practical gift.

National Museum of the Marine Corps Artifact: 2014.XX.1 Bracelet, Identification

Colonel Loren Dale “Doc” Everton retired from the United States Marine Corps on 39 June 1967. He was married to his wife, Delores Everton, for 48 years and passed away in February 1991. His identification bracelet was accepted into the permanent collection of the National Museum of the Marine Corps in September 2014. Assigned the accession number 2014.XX.1, it was donated by Ellen Littlefield in memory of Colonel L. D. “Doc” Everton USMC (Ret.).

[1] “With Uncle Sam: Marine of Crofton Led Plane Research,” Nebraska Mortar & Pestle, December 1944.

[2] Colonel J. Ward Boyce, Editor, American Fighter Aces Album (Mesa, Arizona: The American Fighter Aces Association, 1996), p 260.

[3] John B. Lundstrom, The First Team and the Guadalcanal Campaign: Naval Fighter Combat from August to November 1942 (Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 1994), pp 29-31.

[4] Stephen Sherman, “Marine Corps Aces of WWII.” accessed 3/10/2014 http://acepilots.com/usmc_aces.html.

[5] Richard B. Frank, Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle (New York, NY: Penguin Books, 1990), pp 209-210.

[6] Official Navy Cross Citation, U.S. Marine Corps: General Orders, Board of Awards: December 22, 1948.

[7] Jane Blakeney, Heroes of US Marine Corps 1861-1955.

[8] Sherman, “Marine Corps Aces of WWII.”

[9] Congressional Record, 102d Congress, Tribute to Colonel L.D. “Doc” Everton, February 28, 1991.

[10] Frank Olynyk, Stars & Bars: A Tribute to the American Fighter Ace 1920-1973 (Grub Street, 1995), Everton Bio. (Author Note: Everton possibly shot down 13 total aircraft, but the probable kill leaves this number in flux.)

[11] “Deliver First F2H-2 to Marines,” McDonnell Airscoop (McDonnell Aircraft Corp., Lambert Field, St. Louis, MO), January 1950.

[12] Personnel Records: Loren Dale Everton, U.S. Marine Corps Muster Rolls 1798-1958.

We are always happy to hear from you Get in touch

THE MUSEUM IS OPEN! PLAN YOUR VISIT HERE.

National Museum of the Marine Corps

1775 Semper Fidelis Way Triangle, VA 22172 Toll Free: 1.877.653.1775 |

VISIT

RESEARCH |

LINKS

|

JOIN US ONLINE!

|

©

Copyright 2021. Admission to the National Museum of the Marine Corps is FREE. Hours are 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM every day except Christmas Day.